New report highlights leisure’s crucial role in youth resilience

Barn & unga

21 okt 2025

We all remember the first weeks and months of the pandemic – press conferences, restrictions, and a sudden silence that settled over society. For many children and young people, it was not just about remote learning; it meant an entire world shutting down: football practices, dance lessons, rehearsal spaces, and meeting places disappeared overnight. A new report presents how young people in the Nordic countries were affected by reduced access to leisure activities during the pandemic.

This is the seventh and final report from a project examining the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for children and youth. For about a year, Åsa Gunvén and Monica Johansson from Rapsod have worked on the report, which was launched at a webinar last week. Also participating in the webinar to share their experiences were Sandra Vega, a teacher at Kulturskolan in Uddevalla, and Jonatan Widmark, Vice Chair of the Swedish Association of Youth Councils.

The report presented is an overview of knowledge based on existing research and grey literature, as well as interviews with key actors in civil society and youth organizations, researchers, experts, and young people themselves. The interviewees represent all Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Åland. Monica Johansson holds a PhD from Jönköping International Business School in Sweden, specializing in Political Science, Policy Analysis, and Implementation Studies.

– In this study, I’m a policy analyst and evaluation support, says Monica Johansson. We interviewed people who were directly affected and felt the impact personally – young leisure leaders, youth organizations, umbrella organizations, and experts – a total of 36 semi-structured interviews.

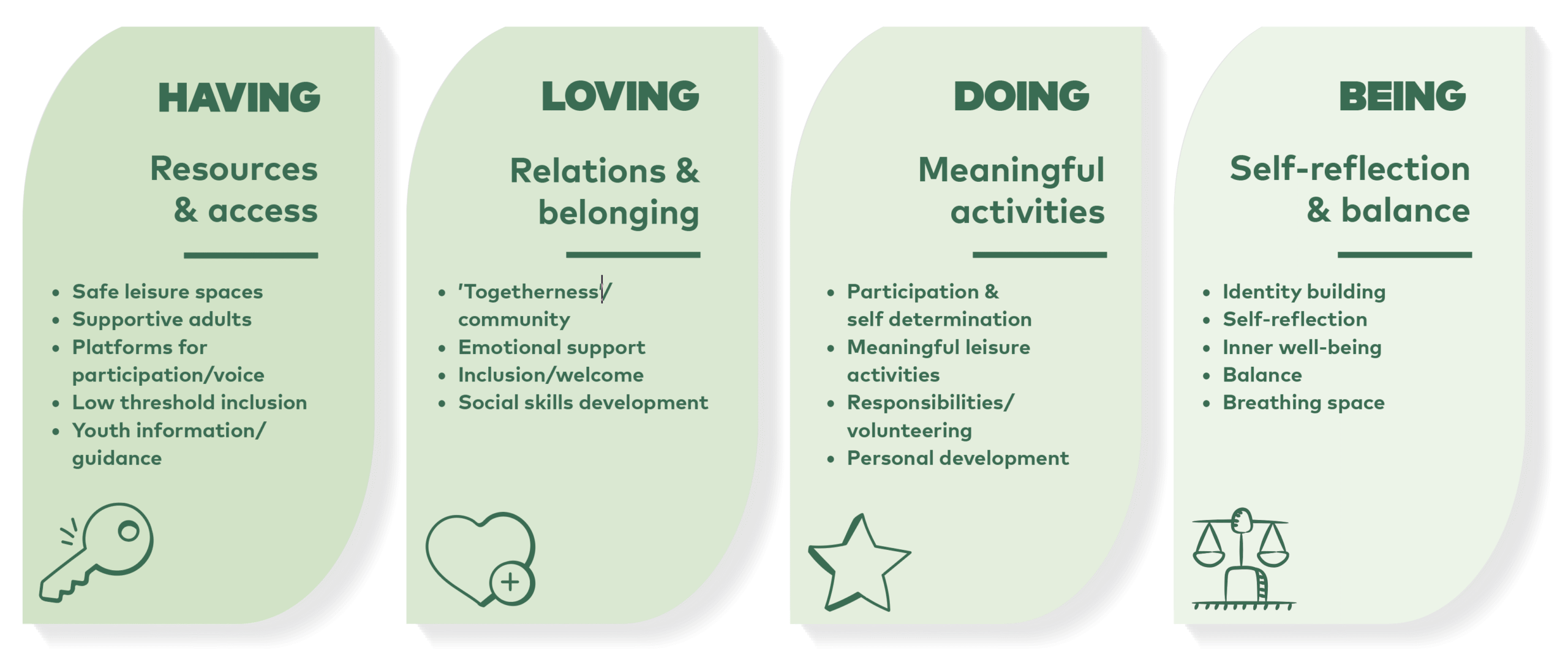

Four dimensions of well-being affected

During the pandemic, the partial or full closure of the leisure sector meant that young people lost access to important factors that would normally contribute to their well-being. In this study, the authors have mapped what negatively affected the well-being of young people. This enabled to identify the key resilience factors that leisure provides, described as

- Togetherness & social interaction,

- Safe leisure spaces & supportive adults,

- Meaningful participation & personal development and

- Low threshold inclusion.

Variations between and within countries

The study explores several research questions about young people’s access to leisure activities, how the sector adapted, and what lessons can be learned for future crises. Åsa Gunvén is a political scientist and coordinator of a regional knowledge centre for open youth work in Stockholm, while maintaining the consultancy firm Rapsod. She has worked at both European and Nordic levels on youth participation development. She also has experience as a youth leader.

So how was leisure affected for young people in the Nordics during the pandemic? According to Åsa Gunvén there is no simple answer. It varied between countries, municipalities, and over time. Bans on gatherings were introduced – extensively, moderately, and periodically. Remote learning and group size restrictions were implemented. Facilities like libraries, youth centres, and sports venues were closed.

– Above all, the changes were rapid, says Åsa Gunvén. New restrictions could be announced every week. Schools were closed at periods in some countries, and most countries introduced remote learning for high school and university students. This made those age groups particularly isolated.

Vulnerable groups excluded

The leisure sector’s quick shift to digital activities may have been a necessary adaptation, but it was a solution that risked excluding the most vulnerable. Many young people also suffered from digital fatigue after long school days in front of a screen, and motivation to log in again in the evening was sometimes low. This is confirmed by Sandra Vega, a dance teacher at Kulturskolan in Uddevalla.

– We noticed it came in waves. At first many students joined, then fewer, because they were screen fatigued. They were online all day for school and then expected to log in again for their leisure activity.

At Kulturskolan in Uddevalla, the check-in round at the beginning of class, where students had a chance to talk and see their friends grew increasingly important.

– Towards the end, that became the most important part – more than the lesson itself – that they got to talk to each other, says Sandra.

The shift also exposed social and economic inequalities: not everyone had access to a computer, stable Wi-Fi, or a private space to participate from.

– Not everyone had the same conditions at home. It was everything from Wi-Fi quality to whether they even had a computer and a microphone. We lost those who struggled with the digital setup, says Sandra.

‘We should have stretched the rules’

Municipalities chose to close youth centres, sports venues, libraries, and swimming pools. And it wasn’t always obvious that the restrictions required a shut down. The municipalities simply chose to be cautious, something Åsa Gunvén believes is worth reflecting on:

– One of the interviewees said: ’We should have stretched the rules as far as possible to benefit young people, but instead we surrendered’. And that is something to reflect on. Should we interpret restrictions with extra caution, or should we try to go as far as possible to ensure access to leisure?

Jonatan Widmark from the Swedish Association of Youth Councils agrees and highlights the role of youth organizations:

– That perspective really stuck with me. Maybe we should have stretched the rules. I would say that if we want to safeguard young people’s perspectives and living conditions, we simply need a stronger youth movement.

Young people were almost entirely excluded from the decision-making that affected their lives. The lack of participation led to restrictions and measures being designed in ways that risked missing what they aimed for. Jonatan believes things could have been better if young people had been involved in decision-making.

– I think people would have realized what the restrictions meant for young people in practice. I think we could have found better ways to communicate with young people, and I think it would have created more of a sense of control to be involved.

But Jonatan stresses that participation must be genuine and warns against ‘youth washing’. Above all, he means, Sweden should follow the example of Norway and Finland and introduce a law requiring youth councils in every municipality and region.

– It seems Denmark might beat us to it, too. I think it would be unfortunate if Sweden ends up being the worst in the Nordics when it comes to youth participation.

Advice for the future

The findings show the pandemic exposed weaknesses in the support provided to young people in the Nordic region. The report emphasizes the vital role of leisure activities in promoting young people’s well-being and resilience – not just through the activities themselves, but through the protective factors they offer. A flexible and well-resourced youth sector is essential to prepare young people for future challenges.

The report offers both insights and advice on how the youth and leisure sector in the Nordic region can be strengthened in preparation for future crises. Here are a few examples:

Ensure the youth perspective in crises

Include young people in crisis management and analyse how different youth groups are affected. Create cross-sectoral working groups with a youth focus and strengthen the role of youth organizations as a link between decision-makers and the leisure sector.

Strengthen youth work

During the pandemic, youth activities proved to be crucial for support and information. The report recommends that youth work be recognized and funded as part of the welfare system, with appropriate resources and legal support. Municipal youth co-ordinators can serve as contact points during crises.

Promote evidence-based development

Establish Nordic competence centres for digital youth work and gather knowledge about factors that strengthen young people’s resilience, to develop the leisure sector on a scientific basis.

The project Nordic co-operation on children and young people’s opportunities for participation and development during the COVID-19 pandemic has come to an end, but the Nordic Welfare Centre will carry the findings from the report forward into future work.

– We will continue to share the findings from the report in various contexts, but we will also incorporate the insights we have gained into other projects we are working on. Not least the projects focusing on young people and digital media, as well as children growing up in low-income families, says Merethe Løberg, Senior Advisor and Project Manager for the project and the report.

The article is a summary of a webinar (held in Scandinavian languages) on October 13.

Relaterade nyheter

Welfare policy

12 jan 2023