4. Conclusion and the way(s) forward

This study explores the role of the leisure sector in promoting the well-being of youth in times of crisis, as well as the potential of leisure as a resilience builder. It is concluded that the policies and restrictions implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic severely reduced young people’s access to leisure activities, resulting in negative consequences for their well-being and personal development. These consequences linger more than five years after the outbreak of the pandemic.

The report shows that the youth and leisure sector adapted relatively quickly. However, as restrictions varied greatly, even within the same municipality, the needs and responses of the leisure sector were diverse.

In this concluding chapter, we will argue that there is solid evidence that preserving access to leisure activities can strengthen the well-being and resilience of young people in times of crisis.

Section 4.1 summarises the main findings from previous chapters, focusing on the gap between young people’s needs and the leisure activities available to them during the pandemic.

This leads into Section 4.2, where we identify a set of resilience factors as essential building blocks for youth well-being. These factors highlight the importance of leisure and give valuable guidance to leisure providers and policymakers on designing, developing, and implementing leisure activities. This guidance is particularly valuable when planning for future crises with the aim of strengthening the resilience and well-being of young people.

The final section 4.3 offers a synthesis of the report’s key findings and presents a set of insights and suggested pathways for enhancing young people’s access to leisure and resilience in times of crisis. Rather than issuing prescriptive recommendations, the aim is to provide inspiration and guidance for policymakers, practitioners, and youth organisations seeking to strengthen preparedness and support resilient structures within the youth and leisure sector.

The proposals and advice are grounded in the voices and experiences of young people, youth workers, researchers, decision-makers and civil society actors across the Nordic region. They reflect both the challenges encountered during the COVID-19 pandemic and the creative adaptations that emerged in response. By highlighting what worked, what was missing, and what could be improved, this section invites reflection and dialogue on how to ensure that leisure remains a protective and empowering space for young people – especially in times of uncertainty.

The insights and advice presented in Section 4.3 are based entirely on the authors’ analysis of various existing good practices and sources, including research and grey literature, as well as over 36 semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders in the Nordic region. Findings and conclusions were substantiated at two workshops involving young people, children’s ombudspersons, researchers, and policymakers. These participants, as well as the interviewees for the study, were also invited to evaluate and comment in an online survey.

4.1 Four dimensions of young people’s well-being affected by decreased access to leisure

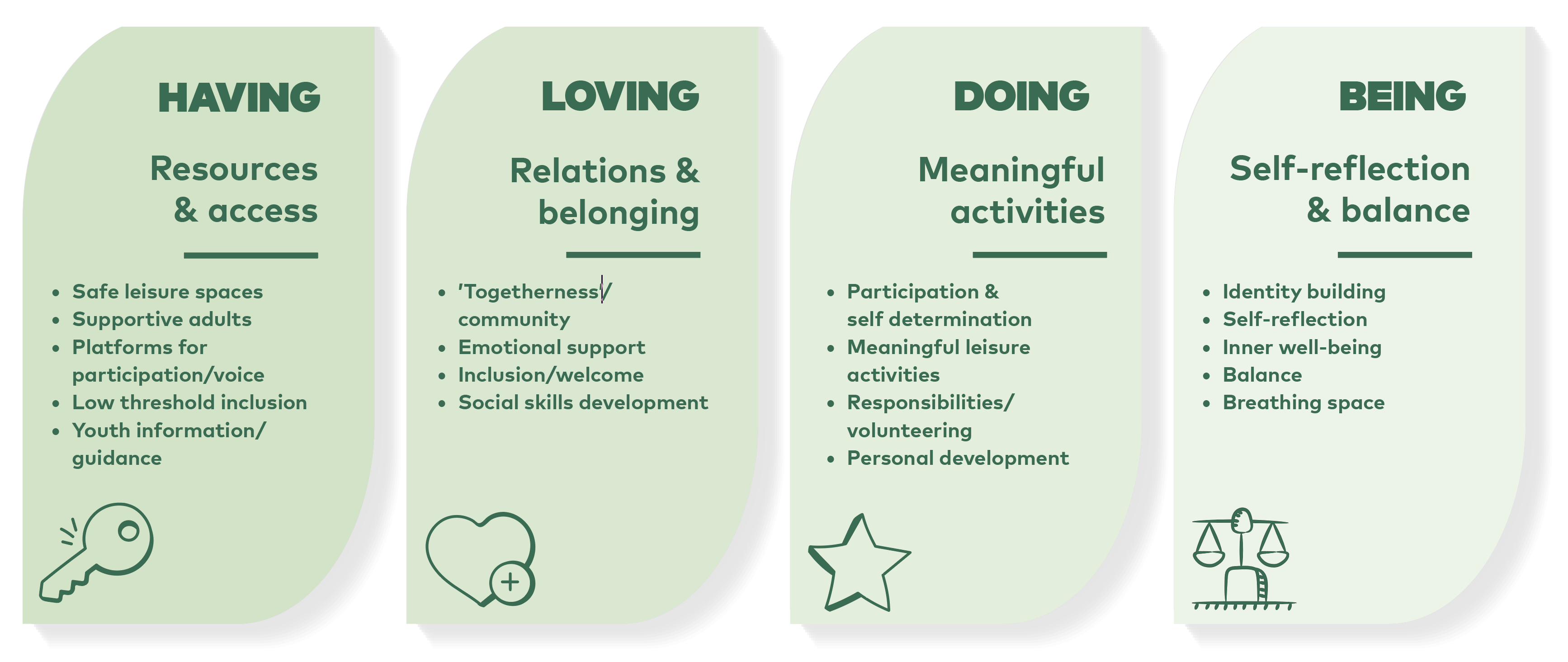

Figure 4.1: The resilience factors of leisure and their contribution to well-being.

During the pandemic, the partial or full closure of the leisure sector meant that young people lost access to important factors that would normally contribute to their well-being. For some young people, particularly those with fewer opportunities, the consequences were significant and irreversible.

In the course of this study, we mapped what negatively affected the well-being of young people as leisure facilities closed fully or partly. This has enabled us to identify key resilience factors that leisure provides.

This model was originally developed by Allardt (1995), further elaborated by Helne & Hirvilammi (2015) and Kauppinen & Laine (2022). The authors of the present report (Gunvén & Johansson) developed it additionally by identifying the critical resilience factors of leisure within its framework (see Chapter 4, Figure 4.1).

These factors are presented in Figure 4.1 and discussed further below with reference to the four dimensions of well-being as Having, Doing, Loving, and Being.

HAVING – resources and access

Young people’s access to leisure activities depended on economic opportunity, social networks, geographical location (including rural and urban areas), and the available activities in the wake of restrictions. As access to safe leisure spaces such as youth clubs and leisure centres was limited, urban spaces, streets, courtyards, parks, and digital spaces instead became places where groups of young people could meet their peers (Kauppinen & Laine, 2022). The increased isolation experienced by many young people, particularly girls, greatly impacted their well-being.

During partial home isolation and in the ‘new’ leisure arenas, young people lacked access to supportive adults and youth leaders from the leisure sector who would have provided critical support and motivation during this time of crisis on multiple levels. While the highly motivated would continue their hobby even if it was digitalised, those who were less engaged would be the first to stop participating, as some of the restrictions removed the possibility of low-threshold activities. (Laine & Malm, 2023)

The closure of open and low-threshold youth centres, in particular, made it more difficult to reach those who did not participate in hobby activities, or who lost access to them during the COVID-19 crisis. Although detached and digital youth work increased in some places, the number of young people reached was still very limited.

Another largely missing resource was easily accessible, youth-friendly information about the pandemic itself and the ever-changing leisure landscape. When access to school nurses and supportive adults in the leisure sector was limited, there was an increased need for information about support mechanisms, such as helplines, for young people.

Finally, several interviewees confirmed that young people were neither included nor invited to participate in interpreting restrictions or adjusting to the new conditions. There were few opportunities for young people to make their voices heard during this transformative period for both young people and society.

The young interviewees identified platforms for youth participation as the resource most adversely affected by the pandemic.

DOING – participating in meaningful activities through leisure

During the pandemic, young people had far fewer opportunities to pursue hobbies and meaningful leisure activities. Governments and authorities prioritised schooling and formal education, and the number and variety of leisure activities and spaces available decreased. Access to non-formal learning, which typically occurs during leisure activities and fosters social interaction and personal development was severely restricted.

Over the past couple of decades, there has been an ongoing trend of fewer young people regularly participating in physical activities, and this trend was reinforced and accentuated during the pandemic among young people in general (Olofsson & Kvist, 2022). The use of social media and screen time surged and has remained high ever since. (Chen et al., 2024; Trott et al., 2022)

Research indicates that the decline in physical activity among young people has had a negative impact on their mental health and their overall general well-being, (Gotfredsen et al., 2024), including social satisfaction and self-esteem. (Juuso, Lehtola & Leskinen, 2022). The latter are features that young people benefit from in leisure activities pursued together with others. Mental well-being is also presented as a feature inherent in ‘Being’ below, since it involves self-reflection and peace of mind.

Taking part in the organisation of leisure activities with others, whether through guided or unguided self-organisation, volunteering, or taking on responsibilities, contributes to young people’s well-being. At a time when there was an increasing need for empowerment and agency, and a desire to take control of one’s life, young people were denied the opportunity for meaningful participation and self-determination.

LOVING – experiencing relations and belonging through leisure

Leisure is an important arena that offers young people opportunities to fulfil their basic social needs, such as experiencing acceptance and inclusion, developing empathy and receiving reciprocity in social relationships. A welcoming atmosphere in which individuals feel that they are seen helps to lower the threshold for participation and build self-esteem.

Several interviewees emphasised the importance of togetherness in leisure activities as a significant contributor to young people’s well-being and an important motivating factor for participation. We have described the many challenges of providing this during the pandemic and the digital adaptations of leisure activities that followed.

The leisure arena is also a place where young people can receive emotional support from their peers and youth workers. The opportunity to talk during activities was partly removed during the pandemic, which had an adverse effect on the most vulnerable young people.

For more than two years, online meetings replaced most opportunities for physical interaction, relationship building and guided development of social skills. While digital technologies partly compensated for limitations in social relations, research suggests that physical distancing disproportionately affected young people aged 10–24, who need peer interaction to develop. (Orben et al., 2020)

Section 2.4 of this report confirmed that the pandemic has had long-lasting effects on young people. These include reduced social skills and social anxiety. This may lead to difficulties when interacting with others and when preventing and managing conflicts.

BEING – space for self-reflection and balance through leisure

Hobbies and leisure activities are important for providing young people with breathing space. They offer an opportunity to take a break from the home and school environments and help young people find balance when they are negatively affected by social pressure and/or school stress.

The enforced social distancing imposed severe limitations in this regard. Interviewees clearly indicated that young people, especially those living in challenging family and home environments, requested such spaces during the pandemic. Few of them were available. (Børns Vilkår, 2022).

The ‘being’ dimension is also related to mental well-being and peace of mind. Both are challenged by a crisis situation and are exacerbated by a lack of supportive structures.

Over a longer period, an increase has been recorded in the number of children and young people suffering from mental health issues ranging from anxiety and isolation to more serious psychological conditions. This trend accelerated during the pandemic, particularly among certain groups of young people.

During their formative years, young people need to explore, experiment with, and define their identity and sexuality. To do so, they need access to youth communities and safe spaces, both of which were lacking due to distancing measures.

Self-reflection, which can be achieved through interaction with friends and emotional support and guidance from youth workers or other supportive adults, has been shown to contribute to young people’s psychological well-being. This need increases in times of uncertainty and stress, such as during a crisis, when it is important to distinguish between perceived and real anxiety.

4. 2 Building resilience through leisure

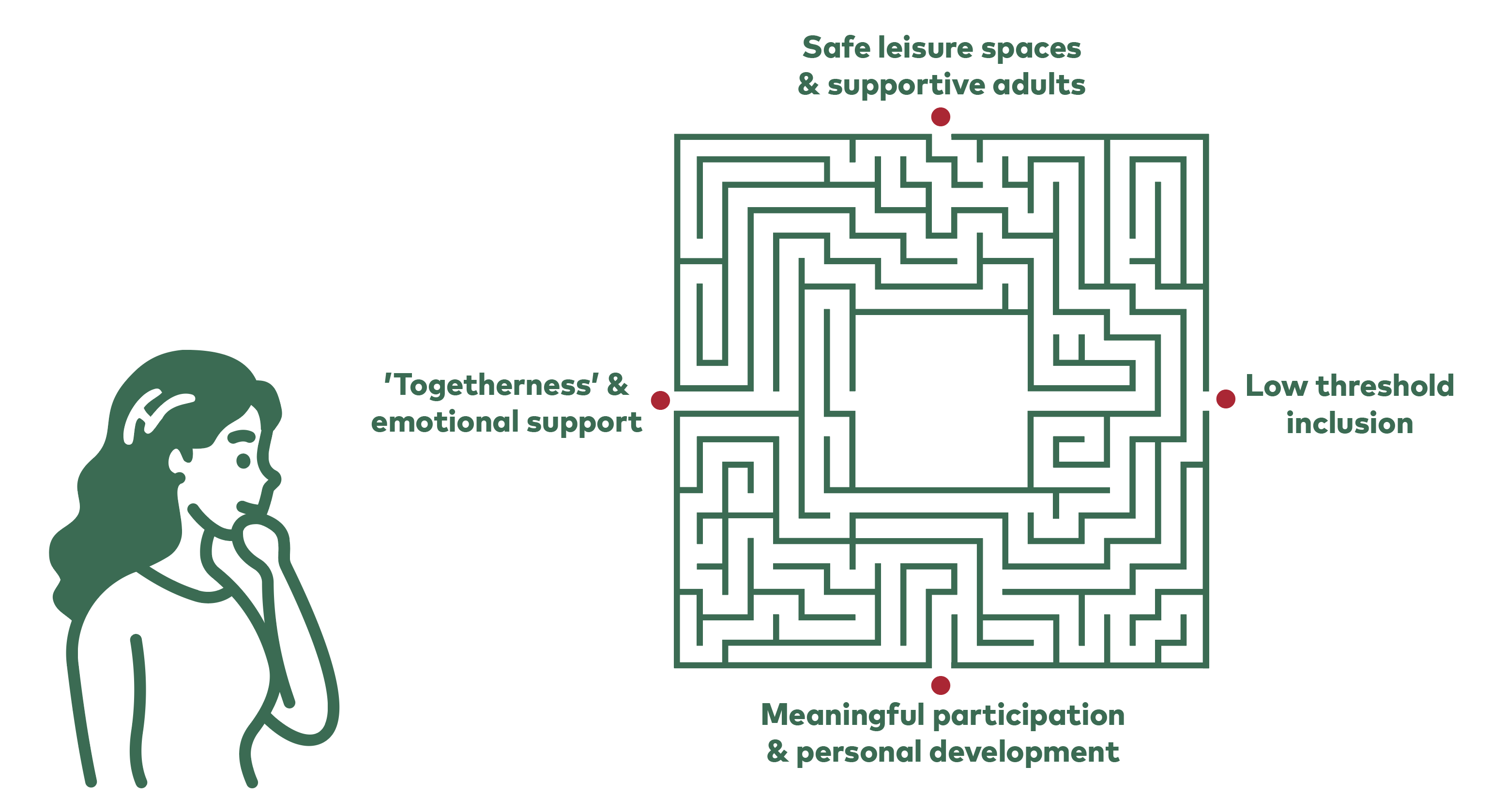

It can be concluded that limited access to leisure resulted in an insufficient supply of the resilience factors outlined in the previous section. This, in turn, had serious consequences for all four dimensions of young people’s well-being. The findings suggest that certain resilience factors are more important than others in times of crisis. These are illustrated in the figure below.

Figure 4.2: Main factors that contribute to resilience through leisure.

During the pandemic, the lack of low-threshold activities and safe leisure spaces, decreased access to supportive adults and emotional support, the feeling of ´togetherness´ as well as opportunities for personal development and meaningful participation. This may have left irreparable gaps in young people’s well-being, socialisation processes, and social skills.

In the event of future crises, the priority should be to ensure the strategic supply of these resilience factors throughout the leisure sector rather than merely ensuring that leisure activities continue. This study suggests paying particular attention to the resilience factors presented in Figure 4.2.

Togetherness and social interaction

One of the young interviewees provided a practical example of how a sense of togetherness and social interaction was lacking in his music classes and elsewhere during the pandemic. He pointed out that offering lessons online is valuable, but it would be even better if the orchestra could have continued to provide a sense of togetherness. The interviewee stated:

‘When you play music, you want to hear others. During the pandemic, no orchestra rehearsals were possible, and group activities were suspended. That was much less fun. You lose the human relationship and contact. The sense of community is compromised, and you feel distant from others.’

The interviewee reflected on the idea that social interaction can be cultivated through conscious effort:

‘I would have liked more opportunities to chat with others about our shared experiences. I even lost my social skills during the pandemic. Youth workers can help by bringing everyone together and starting conversations, not only during a crisis but in general.’

The experience of this young interviewee reflects the findings of this report, shedding light on how the conscious and strategic design of methods and activities can strengthen various resilience factors to varying degrees. One measure that reportedly fostered togetherness and emotional support during the pandemic was setting aside time at the start of an activity for check-in sessions. Looking to the future, one way to further strengthen key resilience factors in music classes, for instance, would be to combine music schools with youth clubs where youth workers are available before and after lessons. Togetherness could be promoted by providing group activities, orchestras for example. Young musicians could be encouraged to participate more meaningfully by being given the opportunity to collaborate on their own project, such as organising their own concert. A similar conscious development process could take place for other types of activities.

One of the young interviewees, who has a neurodivergent diagnosis, emphasised that what she missed most during the pandemic was the opportunity to spend time with and interact with other young people. She said:

‘I missed my Scouts for six months. I was sad and bored. I spent most of my time in bed scrolling through my phone. I missed going out into the forest with my friends. I missed my friends a lot.’

The interviewee describes just how challenging it can be for neurodivergent people to motivate themselves and emphasises the importance of young people having access to social platforms and experience togetherness:

‘Due to my condition, I find it hard to do quiet activities on my own, like painting. I can’t focus on one activity for long. In the Scouts, however, we do a variety of activities, so you don’t get bored. While we’re doing an activity, we talk and interact with each other.’

Low-threshold inclusion

Another resilience factor emphasised throughout the report is access to ‘low-threshold inclusion’. As demonstrated in the report, young people with fewer opportunities are more vulnerable to the negative effects of a crisis. It is therefore vital to minimise barriers to participation in leisure activities, as these young people have a lower threshold for participation due to factors such as a lack of parental support and financial resources. They may also experience discrimination and have health issues and a low self-esteem.

A dance teacher described how young people with mental health issues were the first to be excluded by digitalisation. This illustrates the consequences of raising the participation threshold through activity adaptations in a crisis.

Another interviewee, a young volunteer in civil society organisations, emphasised the importance of lowering these barriers even further:

‘We should remember that we are dealing with vulnerable individuals. Some of them may have been isolated from social contexts for a long time. They suffer from social anxiety and may find leisure activities extremely stressful. So, even if some activities have to be cancelled, those who organise them must learn to be more creative and patient, both during the crisis and when the activities resume. People might not show up at first, but if you are persistent, they eventually will.’

The same interviewee suggested that an effective measure during the pandemic was to be approachable and maintain a welcoming attitude, despite the irregular participation of some young people. Another advice was to continue activities on fixed days at fixed times to keep the threshold low.

Several informants emphasised the importance of keeping youth clubs open, as these provide a low-threshold entry point to leisure activities for young people who are not currently participating. The permanent and local nature of the clubs, and the relationships formed with supportive youth workers, are difficult to replicate in a digital youth work setting.

Maintaining resilience factors in digitalised leisure

Another area that requires further consideration regarding resilience factors is the digitalisation of leisure activities. In the event of future crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, digitalisation will provide ample opportunities for the leisure sector to continue many of its activities online. Therefore, it is highly relevant to explore the potential of digitalisation while maintaining resilience factors such as active participation, togetherness, and access to supportive adults. Further research in this area, practical toolkits, and competence building would all be highly valuable going forward.

4.3 Insights and pathways for strengthening leisure and resilience in times of crisis

In conclusion, the need to strengthen the resilience of the leisure sector must be widely acknowledged in the face of future crisis.

The insights that have emerged throughout this study have been categorised under the following five main topics: A) Being prepared; B) Policy development; C) Structures for coordination; D) Communication; and E) Adaptations. Advice for enhancing young people’s access to leisure and resilience in times of crisis follows each set of insights. This section aims to inspire and guide policymakers, practitioners and youth organisations seeking to strengthen preparedness and

support resilient structures within the youth and leisure sector.

The insights that have emerged throughout this study have been categorised under the following five main topics: A) Being prepared; B) Policy development; C) Structures for coordination; D) Communication; and E) Adaptations. Advice for enhancing young people’s access to leisure and resilience in times of crisis follows each set of insights. This section aims to inspire and guide policymakers, practitioners and youth organisations seeking to strengthen preparedness and

support resilient structures within the youth and leisure sector.

A. BEING PREPARED

1. Contingency planning for leisure

💡Insights: This report concludes that governments and policymakers in the Nordic countries did not pay enough attention to the important role played by the leisure sector in promoting resilience among young people during the COVID-19 pandemic. The crisis revealed significant deficiencies in the contingency planning of the Nordic youth and leisure sector.

Both municipalities and youth/leisure organisations were largely unprepared, lacking plans to continue activities and implement necessary adaptations. One respondent stated:

‘During the pandemic, we had to invent solutions as we went along, during a crisis. Next time, we must be prepared; therefore, contingency plans need to be developed now.’

Advice:

✅ Include young people’s needs in contingency planning . Contingency plans at local and national levels should include a chapter on the holistic needs of children and young people. Developed with the involvement of young people and the leisure sector, these plans should cover general structures and tools for maintaining access to meaningful participation, safe leisure spaces and adult support.

✅ Involve the leisure sector in the planning process. The capabilities and possibilities of the various parts of the leisure sector should be used in the contingency planning, building on the complementary roles of the private, public, and civil sectors. While encouraging cross-sectoral collaboration, the independence of civil society organisations to act according to their own vision and priorities must be respected. For example, civil society organisations should not be expected to perform tasks or assume responsibilities outside their remit.

✅ Strengthen contingency planning within the leisure sector. To enhance the leisure sector’s ability to respond effectively in times of crisis, the contingency planning and organisational adaptability of municipal youth work and civil society must be strengthened. This includes joint initiatives to develop adaptation skills and infrastructure (e.g., digitalisation), as well as organisational-level contingency planning.

2. A legal framework for youth work

💡Insights: One respondent explained:

‘We need a clear, shared understanding of what youth work is and what it should achieve. In a crisis situation, a Youth Act would help us decide what adaptations to make, as it would define a shared goal that is legally supported.’

Finland is the only Nordic country to have a Youth Act. This legislation aims to support young people’s personal development and independence, encourage active citizenship and participation, and enhance their living conditions. The Act establishes provisions for youth work and requires cross-sectoral co-operation to ensure that young people – defined as individuals under the age of 29 – receive the necessary support and opportunities.

Advice:

✅ Establish a legal framework for youth work. Having a legal framework for youth work, which includes its aims and standards, would clarify its role in building resilience among young people. It would also emphasise the importance of youth work as a critical resource in times of crisis.

3. Research and lessons learned from youth work and leisure

💡Insights: This study identified a lack of examples of lessons learned from youth work and leisure activities during the pandemic. There is also a lack of documentation and follow-up relating to the development of resilience within the sector, which could facilitate knowledge-based development of youth work practice and strengthen resilience among youth. Most of the examples found were narratives of local, specific, and sometimes isolated events. Had references to promising practice, research, and lessons learned been available, they could have served as input for national-level dialogues on good practice across the Nordic countries.

Advice:

✅ Expand the scope of youth research and collect practical knowledge. The field of youth research has the potential to expand its scope to cover a much broader range of leisure-related issues, including factors that promote resilience. It is also crucial to collect, preserve, and utilise practical knowledge, experience, and lessons learned from youth work relating to leisure during times of crisis. This is particularly important for improving the delivery of the identified resilience factors based on evidence.

B. POLICY DEVELOPMENT

1. A youth perspective in policy development at national level

💡Insights: This report provides numerous examples of the negative consequences for young people of not having access to leisure activities and the resilience factors they provide during the pandemic. At the same time, young people were largely excluded from policy development. Although several national youth councils were consulted, there were no structures in place to ensure their meaningful inclusion.

The report’s findings also show that lockdowns and restrictions disproportionately impacted groups of young people with fewer opportunities. One respondent stated:

‘Young people’s influence was generally missing from policy processes, yet the restrictions placed on children and young people with disabilities were particularly severe.’

These adverse effects could have been mitigated or avoided had a youth perspective and consequence analysis for different youth groups been implemented.

It is also necessary to include young people in local co-ordination structures. See section C1 for more information.

Advice:

✅ Incorporate a broad youth perspective in national and local policy measures. Youth-led organisations and/or well-functioning youth councils should be invited to participate in designing the crisis response. For this to be meaningful, they must be involved from the outset and throughout the entire process, and their contributions must be given appropriate consideration. Such structures should be established as part of contingency planning well before a crisis hits. Other important stakeholders in the youth sector, such as municipal youth services, children’s rights organisations, and schools, should also be included. It is particularly important to involve different groups of young people with fewer opportunities in the analysis of the consequences of the crisis response, as they are adversely affected by the closure of leisure facilities. The direct voices of young people should also be included in the process, particularly within local contexts.

2. Adoption of flexible, yet sturdy, regulations to maximise youth’s access to leisure

💡Insights: Some youth workers indicated that restrictions were sometimes applied across entire countries or regions, regardless of the local infection control situation. As one respondent stated:

‘National statistics from big cities would form the basis for excessively harsh restrictions in areas that might not have needed them at all.’

Another interviewee made a similar point:

‘Some premises that were immediately closed at the outbreak of the pandemic could have remained open. The organisers would have implemented restrictions on group sizes and social distancing to prevent the spread of infection.’

Advice:

✅ Develop tailored policies. One-size-fits-all regulations should be avoided. The development of tailored solutions that maximise young people’s access to leisure activities should consider local knowledge, resources, and specific needs. Rather than prohibiting leisure activities, regulations that limit them should be developed to allow for innovation and adaptation. These regulations should also remain stable over time, enabling the leisure sector to develop adequate adaptation strategies and providing stability for young people and youth workers.

3. Making use of school as a leisure arena

Insights: In Chapter 3, informants mention arrangements whereby school premises were used for leisure activities in the afternoon as a measure to adapt to the pandemic. In line with the Finnish model gaining popularity in the Nordic countries, smaller groups or cohorts who were already meeting during the school day were permitted to continue doing so for these activities. This prevented the spread of infection while enabling social interaction during free time.

Advice:

✅ Make use of school venues as safe spaces. School venues should be made more widely available as safe spaces for leisure activities and socialising. During a pandemic, there is also potential to use school ‘cohorts’, i.e. groups of young people, for leisure activities and youth participation without increasing health risks.

4. Supporting a quick start-up and compensation phase

💡Insights: As society begins to open up again after a period of crisis, it is crucial for leisure providers to quickly start offering in-person activities again. Every week that passes makes re-engagement more challenging as social anxiety increases. As one informant stated:

‘It only takes three months to completely lose the relationship with a young person.’

The interviewees emphasised the importance of grants during the opening-up phase and highlight the challenges the sector faces in scaling up quickly after a crisis. Chapter 3 of this report discusses how youth workers used detached youth work to meet and keep in touch with young people during the pandemic, and how this lowered the threshold for re-engaging with leisure activities and spaces.

Advice:

✅ Provide the leisure sector with necessary resources for a quick restart. Once society starts to open up again after a crisis, it is crucial that the leisure sector is provided with the necessary resources to re-engage young people in social activities and leisure pursuits without delay. Detached youth work has proven to be an effective means of building bridges to leisure activities and compensating for deficits in social competence and habits among young people in the aftermath of the pandemic. Funding for summer camps and grants to kick-start the leisure sector and reengage youth are also important, particularly at a local level.

C. STRUCTURES FOR COORDINATION

1. Structures for meaningful youth inclusion at local level

💡Insights: Structures for youth participation can enhance the leisure and youth sector’s ability to maintain operations throughout the crisis, as well as facilitating a quicker restart when society reopens. This is because the response can be tailored to the needs of different youth groups and the specific circumstances of each area. Several interviewees emphasised that stable structures must be in place prior to a crisis for youth participation to be possible when the crisis hits, and that such stable, well-functioning structures are scarce. In Norway, for example, local youth councils are legally required, though their roles, composition, and effectiveness can vary between municipalities. However, one workshop participant warned that it is all too easy to abandon useful participatory structures in times of crisis in favour of other concerns.

Several interviewees emphasised the importance of participatory structures that include both unaffiliated young people and broader youth representation through youth organisations. One respondent also highlighted the necessity of addressing the ‘right’ young people – those who are concerned about the process.

Advice:

✅ Establish and strengthen local youth participation structures. Well before the next crisis hits, representative local youth participation structures managed by young people themselves need to be established. When identifying the needs of young people and developing crisis measures, it is important to consult those who are already active in the leisure sector, as well as those who are not. Examples of structures that can be adopted for crisis response include local youth councils and permanent national and local youth working groups.

2. A youth working group for coordination

💡Insights: Our report emphasises the importance of young people having access to leisure activities for their well-being and resilience. This requires collaboration between all youth stakeholders from different sectors, including young people themselves. A Norwegian respondent provided the example of a municipal-level crisis response task force formed during the pandemic, comprising public bodies and civil society organisations.

Advice:

✅ Establish youth working groups for comprehensive crisis management. The establishment of a dedicated youth working group comprising representatives from the youth and leisure sectors, relevant public services, and young people themselves would facilitate more comprehensive crisis management in relation to youth well-being. Regarding leisure, the group could promote cross-sectoral co-operation, identify the sector’s needs, and ensure access to leisure activities.

3. Resourcing sector-specific hubs/umbrella organisations

💡Insights: During the COVID-19 pandemic, umbrella organisations such as youth councils, sports associations, disability organisations, and youth work networks played a vital role in enabling their members to continue providing leisure activities. Their activities included updating and translating restrictions, developing skills and competencies, and offering tailored support via hotlines.

Advice:

✅ Allocate funding and resources for umbrella organisations. Directing resources towards umbrella organisations to strengthen their supportive role would better equip the leisure sector to withstand crises. The sector’s ability to adapt its activities could be enhanced further by providing these umbrella organisations with adequate innovation resources and financial support, utilising their network-based knowledge and outreach.

4. A youth coordinator at municipal level

💡Insights: This study reveals that the leisure sector currently lacks the necessary resources, infrastructure, and support structures at a local level to adequately adapt in times of crisis. To access the municipality, its resources and networks, leisure providers need entry points and adequate human resources. This can be challenging, particularly for small organisations with limited staff.

Advice:

✅ Appoint a municipal youth coordinator. Appointing a municipal youth coordinator before or during a crisis would enable youth leisure providers to access support and resources more easily, helping them to adapt and avoid closure. Such coordinators could foster cross-sectoral co-operation, identify needs within the sector and resolve them, and facilitate the provision of venues and other essential infrastructure throughout the crisis. They could also ensure that young people have access to adequate information about local leisure opportunities, for example by setting up a dedicated website.

D. COMMUNICATION

1. Leisure-sector specific guidance

💡Insights: In interviews, many leisure providers across the Nordic region said that they found it challenging and frustrating to implement government regulations and recommendations effectively. This resulted in them being overly cautious and choosing closure over adaptation. For instance, many municipalities opted to shut public leisure venues, including sports halls and youth centres, when other measures could have been implemented to keep them open.

Advice:

✅ Provide guidance and minimise uncertainty. To maintain leisure activities and keep leisure spaces open, it is crucial to minimise uncertainty over what is permitted. Any new restrictions or regulations must be accompanied by leisure-specific guidance for municipalities and leisure providers to prevent misinterpretation or the unnecessary severe application of restrictions.

2. Providing adequate youth information

💡Insights: Young people need access to information tailored specifically to them to fulfil their rights and needs. Several interviewees suggested that the need for information increases during times of crisis.

One interviewee reflected on the importance of positive communication about participation during a crisis:

‘We should have run many more social media campaigns targeting young people to promote the idea of continued participation, given that public discourse was only highlighting dangers and distancing measures. We could have played a role in counterbalancing this.’

Advice:

✅ Provide youth friendly accessible crisis information. Information related to crises and young people’s well-being should be made available at national level. This should include clear and up-to-date details about leisure opportunities, emotional support services, and other relevant resources. To be effective, the information must be communicated in a way that is accessible and meaningful to young people – using language, formats, and channels that resonate with them and reflect how they typically seek and engage with information.

This communication should be part of a proactive youth information strategy, supported by a well-resourced leisure sector. Youth organisations should also be encouraged – and publicly funded – to run campaigns that promote participation in unstructured, semi-structured, and structured leisure activities, particularly during and after times of crisis.

This communication should be part of a proactive youth information strategy, supported by a well-resourced leisure sector. Youth organisations should also be encouraged – and publicly funded – to run campaigns that promote participation in unstructured, semi-structured, and structured leisure activities, particularly during and after times of crisis.

3. Using public communication to prevent the risk of stigmatising youth

💡Insights: Some of the interviewees said that young people seeking to socialise were sometimes stigmatised as ‘lawbreakers’ and potential carriers of the virus. This perception also affected the leisure sector, causing it to adopt an overly cautious approach. As one respondent stated:

‘In the Faroe Islands, people kept an eye on each other and were quick to judge others’ actions. While public debate focused on physical health, the risks of loneliness were overlooked.’

One of the interviewees gave an example of how public communication helped mitigate the stigmatisation of young people:

‘The Norwegian prime minister’s speech emphasised the responsibility that young people carry on behalf of others. This has certainly helped reduce the tendency to publicly shame young people, even here in Denmark.’

Advice:

✅ Communicate in support of of participation. Public communication should proactively address the fears and concerns of young people, their families, and other citizens regarding participation in social activities during times of crisis. Public discourse should focus not only on physical health, but also on the risks of loneliness and social marginalisation, and other aspects of young people’s well-being.

4. Building trust with parents and caretakers

💡Insights: This report highlights that the public information provided about the necessary precautions and restrictions during the pandemic often caused uncertainty among parents and carers. Parents needed clear, reliable information about safety measures and the activities available for their children. Building this trust is crucial to ensuring that all young people, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, can access and benefit from leisure activities. At the same time, interviewees emphasised the challenges involved in establishing and maintaining the necessary relationships and information flow with carers.

Advice:

✅ Provide easily accessible information to build trust with caretakers. In a crisis, both municipalities and leisure providers must build trust with parents regarding youth leisure activities. This involves establishing relationships and providing easily accessible, multilingual information about the leisure opportunities available to their children, as well as the safety measures in place for these activities. This is particularly important for young people with disabilities, those with family members in risk groups, and those from migrant backgrounds.

E. INFRASTRUCTURE FOR ADAPTATIONS

1. Making safe and accessible outdoor leisure spaces available

Figure 4.3: Safe outdoor leisure spaces.

💡Insights: One of the expert informants of this study asked young people how they imagined their own space during the pandemic. She recounted:

‘They described a safe place with supportive adults present to ensure inclusion and non-discrimination. Some basic services should be available, such as mobile phone chargers, internet access, a microwave, and a kettle. Youth said they wanted to use the space to organise activities or simply hang out.’

Leisure organisers also identified the need for shelters to enable them to continue their activities outdoors in the Nordic climate.

Advice:

✅ Provide safe leisure spaces . Regardless of the crisis, safe leisure spaces managed by supportive youth workers should be made available to enable young people to socialise and organise activities safely. These spaces could be outdoors. The leisure sector also needs adequate infrastructure – such as outdoor spaces with lighting – to enable it to continue its activities safely.

2. Provide adequate resources to enable adaptations

💡Insights: The report notes that the adaptations required in the leisure sector during the pandemic were partly resource intensive. A lack of resources meant that these adaptations were not as innovative or high-quality as they could have been. Also, valuable initiatives such as detached youth work and high-quality digital youth work were not implemented on a large enough scale. Furthermore, informants highlighted the difficulty of finding larger premises in which groups of young people could organise themselves, play sports, and take part in other leisure activities while observing social distancing measures. Adequate venues were lacking, which hampered innovation and limited options for adaptations, particularly when group sizes were limited.

Advice:

✅ Allocate additional resources and provide infrastructure. Additional resources will be required to implement the necessary adaptations within the leisure and youth sector during times of crisis. These resources must be allocated based on the sector’s identified needs, ensuring they are disseminated to smaller organisations and initiatives, too. It is crucial to provide adequate infrastructure, such as venues and digital resources, as a lack of this infrastructure creates bottlenecks for activities across the entire sector.

3. Use youth workers and youth centres as resources

💡Insights: During a crisis, when the needs of young people are unpredictable and change rapidly, youth centres can be valuable hubs for promoting the well-being of children and young people. They have the ability to increase the scope and level of activity, combined with professionalism, flexibility, knowledge of young people, and access to them. Ukrainian informants referred to local youth centres as an indispensable resource for young people and wider society in a crisis situation.

One interviewee summarised the potential role of a local youth centre as a resource centre:

‘We are a resource for young people by supporting them in what they want to do and achieve; for youth organisations that want to use our premises; for vulnerable young people and for the local society and the municipality. The pandemic highlighted that local youth centres are needed, and today we are even experiencing an increased request for our support from the municipality.’

Advice:

✅ Redirect, scale up, and resource municipal youth work. In a crisis, there is potential to redirect, scale up, and resource municipal youth work, including local youth centres and youth workers. The aim is to increase young people’s access to resilience factors through leisure activities. With adequate responsibilities and resources, municipal youth services can also support other essential municipal activities during a crisis. These include public health, democracy engagement, volunteering coordination and support

for hobbies and youth organisations.

for hobbies and youth organisations.

4. Develop knowledge hubs at Nordic level

💡Insights: In Finland, centres of excellence have provided crucial support for digital youth work and youth information work, both before and during the pandemic (e.g., Verke and Koordinaatti). However, today the centres are closed, and there has been a general retreat from digital youth work and the development of digital youth work competencies within the Nordic region. This leaves us ill-prepared for an impending crisis in which youth information and digital youth work are likely to remain vital.

Advice:

✅ Explore the possibilities for establishing youth work centres of excellence. The potential for setting up Nordic centres of excellence to support evidence-based youth information and digital youth work should be investigated. If such hubs are set up, they must be maintained at all times – including periods of stability – to ensure a high level of preparedness in the event of a crisis.