3. Crisis response in the youth and leisure sector

The pandemic tested society’s ability to withstand and adapt to rapid change. As described in Chapter 2, the leisure and youth sector faced a number of challenges that required swift and flexible responses. Youth and leisure organisations adapted relatively quickly. These adaptations helped ensure that young people could continue to access leisure activities and contributed to reducing the negative impact of the pandemic on the sector and on young people’s everyday lives.

As restrictions varied considerably — even within the same municipality — the responses of the sector were highly diverse. The illustration below summarises the measures taken in the Nordic countries to ensure young people could continue to access leisure activities and to mitigate the negative impact of the pandemic on the leisure sector.

Figure 3.1: Changes made in the Nordic region during the pandemic to tackle challenges in the leisure sector.

This chapter begins with an insight into the workings of a Danish youth centre. It then provides an overview of the various adaptations implemented across the Nordic region during the pandemic.

Sections 3.2–3.5 will examine each type of adaptation in greater detail. Digitalisation has been given special attention because it was a particularly extensive and complex form of adaptation for promoting the well-being and resilience of young people.

Innovative adaptations at a Danish youth club

A Danish youth worker described how a youth club had quickly adapted to the new conditions imposed by the pandemic. This involved targeting young people with special needs and using digitalisation and detached youth work to reach those who were forced to stay at home.

The club usually caters for around 250 users aged 10–18, and it is open for 28 hours a week to young people from local schools. Some of the visitors are young people with fewer opportunities, including those facing issues such as substance abuse, economic hardship, and psychological challenges such as stress and anxiety. Under normal circumstances, a variety of free activities are offered, including:

- A creative room, a music room, and an e-sport room, all guided by professional staff.

- Classics such as billiards, football, and table tennis.

- Free dinners twice a week and a light lunch every day.

- A focus on providing a safe place to be and have fun, with a strong emphasis on ‘hygge’ (cosiness/well-being), while providing protective factors such as emotional support, guidance, and encouragement.

The interviewee narrates:

‘Our club prioritises creating an environment where young people can “be together in their differences” through activities. We also try to attract youth who might otherwise be on the streets, without access to other leisure activities, by providing a positive alternative.’

While most young people were staying at home during the COVID-19 pandemic, this club opened its doors to around 40 young people with special needs whose parents or carers were unable to provide necessary support, such as helping with home schooling. At the youth centres, these young people received support with distance learning, as well as access to youth workers and activities. A 38-page guideline from the municipality ensured their safety. The informant stated:

‘The initiative to keep the youth centre open for a group of young people with greater needs was highly successful, and the protective measures worked well – nobody fell ill.’

The youth workers were keen to reach out to young people who were unable to attend the youth centre during the pandemic. The interviewee recounted:

‘We drove or cycled to the homes of those who were unable to leave. We gave them a T-shirt bearing the name of our youth club and a letter of encouragement. We told them that we missed them and that they would be welcome back to the youth club after the pandemic. We also invited them to meet us on digital platforms such as Fortnite, an online game and platform. Together, we dreamed and planned what we would do once society reopened.’

Youth workers would organise outdoor activities where we could be together while also being apart such as walking, biking, canoeing, and fishing. At the same time, they would offer opportunities for dialogue and emotional support.

The municipality played a key role in helping to reach parents via the school. This was important as many parents did not allow their children to go out. It also suggests official recognition of the value of leisure activities and coordination.

With 210 out of 250 young members unable to come to the club, the operations were quickly moved online. Digital efforts included:

- Starting an online youth club that allows for virtual ‘dates’ and activities in games such as World of Warcraft or Fortnite. However, the interviewee mentioned these as a fill-in rather than a full replacement.

- Organising and facilitating shared experiences, such as watching and discussing Netflix films together, or taking part in baking activities and sharing the results online.

- Engaging in Instagram activities, social media interactions, and Twitch streams.

- Utilising Microsoft Teams and Discord for meetings and group chats.

- Producing podcasts for young people.

- The youth workers of the municipality started a nationwide Facebook forum for practitioners to share good practice and boost morale.

The informant concluded:

‘While our centre was very active during the pandemic, the situation varied greatly from one municipality to another. Some did nothing to adapt, others did a lot.’

3.1 Digitalisation

One of the most common responses to the restrictions imposed in the Nordic countries was to convert physical leisure activities into digital formats. As one expert explained:

‘For youth organisations, digitalisation was a matter of “do or die”.’

The focus varied between countries and leisure contexts, and the adaptations were implemented with varying degrees of success. Although many leisure activities could be digitalised relatively easily, it remained challenging to ensure factors that contribute to resilience, such as ‘togetherness’, peer support, and low-threshold inclusion. An informant representing a sports organisation said:

‘As the threshold for participation increased with digitalisation, we immediately lost our most vulnerable participants.’

Digital municipal youth work

Municipal youth services in the Nordic countries created virtual youth centres, where youth workers organised activities such as quizzes, film nights, and creative workshops (e.g., digital art and music production) via video chat platforms. (Virtanen & Olsen, 2022). As one youth worker from Norway described:

‘Like most other youth clubs, we created new digital meeting spaces on social media platforms such as Discord, Snapchat, Instagram, and Facebook. We also offered young people a course in how to create a podcast. The podcasts featured interviews with artists and musicians. It was a great success.’

Discord was widely used in youth work during the pandemic. This platform for instant messaging, voice, and video chat allows users to communicate privately or within virtual communities called servers. These servers are organised into different text and voice channels, enabling groups to talk, share media, and participate in activities together. Although originally designed for gamers, Discord is now widely used by diverse communities for various purposes.

Youth centres across the Nordics used Discord to offer activities such as watching movies or gaming together, taking part in leader-led activities and workshops, and using a digital or phygital (physical and digital activities combined) ‘maker space’, where young people could work on their projects. Here youth could also take part in conversations about a variety of topics or meet up in smaller, more intimate groups. Some channels were about pets, others about food and recipes, photography, film, or literature. One youth worker mentioned a channel dedicated to cooking where:

‘People would bake something or prepare a meal and then show the results to other participants.’

Although young people were not heavily involved in designing the overall digitalisation strategies, they played a proactive role in shaping the activities and topics offered at digital youth centres and on Discord servers. As one digital youth worker stated:

‘We do things together that the young people have decided on. That works best.’

Discord servers were also used to compensate for a lack of adult contact outside the home. A youth worker from Finland explained:

‘We heard from young people that many of them needed to talk to adults who weren’t their parents or close relatives, so we set up an online service on the Discord server.’

Chats could take place either during dedicated support hours or in a separate digital room during activities.

Several of the interviewed youth workers emphasised the importance of involving active young people as youth moderators to create a safe digital space within the Discord server. Thanks to the automatic monitoring and notification function, the servers could remain open 24/7 – even when no youth workers were online.

Young people also played an active role in developing innovative tools. For example, a Danish youth worker described how girls came up with different ways to meet on gaming platforms and created unique avatars for socialising. Rather than playing the game itself, they used the avatars to meet, hug each other, and dance – a way for them to feel close to each other, albeit virtually. Such innovations are important in including girls, who tend to use more competitive social media sites or single-player games for online leisure activities. Boys, on the other hand, tend to spend more time gaming live with friends and communicating in group chats. For this reason, there is a need to develop more group-based games and alternative forms of digital interaction for girls. Virtual reality is another area worth exploring in this respect.

In Norway, expertise in digital youth work was brought together in Trondheim, where 15 youth workers joined forces to set up a national Discord server that an individual local youth centre could not hope to match in terms of scale and outreach. The Trondheim team also supported local youth workers, helping them to set up their own Discord servers.

Similarly, in Finland, a national Discord server enabled large-scale digital participation by pooling resources and providing more youth workers and content, courtesy of Verke. Verke, the Centre of Excellence for Digital Youth Work, was established in 2011 and closed in 2024. Interviewees have referred to Verke’s knowledge and expertise as being instrumental in the digitalisation of youth work processes during the pandemic, not only in Finland, but in other Nordic countries, too.

The digitalisation of youth work also presented many challenges. One informant describes:

‘Maybe only four out of a hundred Discord servers used by youth centres worked well. You need the skills to run it, and digital youth work skills were scarce among the youth workers.’

In the Verke 2021 digital youth work survey, youth workers identified insufficient working hours as well as a lack of skills and objectives as the main challenges in digital youth work. The report concluded that, although digital skills had improved relating to devices and applications, the pandemic had not led to an increase in digital youth work competencies.

Considerable effort was invested in training and developing skills throughout the pandemic, particularly by the umbrella organisations of municipal youth work. For instance, Verke in Finland hosted a Discord server for 2,500 youth workers, facilitating peer-to-peer learning and offering several training sessions and lectures each week. At the same time, however, several informants described it as challenging, if not impossible, to establish the necessary infrastructure and skills once the crisis had hit and the shift to online work had occurred. Another informant reflected on the issue of working hours in digital youth work:

‘One challenge we initially faced when going digital was that many youth centres closed and the youth workers were laid off. Those who are not familiar with digital tools may think that fewer personal resources would be required for online activities than for our everyday physical work. Unfortunately, it’s not that easy. Access to at least one youth worker needs to be guaranteed in order for the space to be safe, and one-to-one counselling and emotional support sessions are needed. So, the youth club, its activities, and its staff needed to go digital without being downsized.’

Although digitalisation was the main adaptation in youth work, digital initiatives were largely abandoned as soon as society started to reopen after the pandemic. As one of the informants mentioned:

‘In the next crisis, we’ll have to start from scratch with regard to digitalisation.’

A former employee of a digital youth work hub in a Nordic country said that his hub’s staff numbers were reduced from 15 to fewer than one after physical leisure activities reopened following the pandemic. Another example of a stalled digitalisation initiative was the closure of Verke in Finland.

Digitalisation in leisure and youth organisations

Youth and leisure organisations also underwent extensive digitalisation.

According to a digital youth work expert interviewed for this report, Youth Against Drugs in Finland was one of the first youth organisations to engage with young people through interactive digital youth work. For example, they ran phygital challenges in which young people had to go outside to complete tasks and then share their experiences online. This method was adopted by others throughout the pandemic.

Hobby associations across the Nordic countries launched digital training programmes and challenges aimed at young people. These included online dance classes, at-home training sessions led by youth leaders via live stream or video, and step challenges in which young people competed to take the most steps outdoors using apps. Other examples include individual orienteering with remote GPS monitoring and coaching, as well as virtual cheerleading competitions and training sessions on social media platforms. Organisations focusing on art, music, theatre, and programming for young people moved their courses and workshops online. Young people learned to play instruments, write stories, code games, and participate in virtual theatre projects from home. (Guðmundsdóttir & Larsen, 2022)

Many after-school clubs and youth associations in the Nordic countries organised digital game nights and tournaments of popular e-sports titles, as well as virtual LAN parties, via platforms such as Discord and Twitch. (Karlsson & Nielsen 2021)

In Sweden, Save the Children (Rädda Barnen) was one of the initiators of the DigiFritids.se platform, which is a safe digital space for children aged 6 to 12 to enjoy their leisure time. There was also a section called ‘Support Ice Cream’, where children could access information about their rights and get in touch with safe adults, for example via the BRIS (Children’s Rights in Society, Sweden) chat service.

Some organisations managed to incorporate a social element into their activities. For instance, young people and leaders would engage in drawing activities together while listening to background music. This approach aimed to foster a sense of togetherness in an online setting, rather than focusing solely on performance, competition (as in gaming), or instruction (as in a drawing class). (Kauppinen & Laine, 2022)

A dance teacher described how she preferred to stream dance classes, rather than provide participants with training videos. She said:

‘I told the participants that it doesn’t matter if you’re in the middle of the living room with limited space for dancing and young children running around. The important thing is that we do this together.’

She also included a check-in round at the start of each class. This exercise grew in importance and length over time.

These examples demonstrate the advantages of live digital interaction over asynchronous interaction, in which users do not need to be online at the same time. Horizontal activities, in which the youth leader creates an environment for ‘doing together’ rather than ‘giving instructions’, were also referred to by interviewees as successful methods for fostering togetherness online and build resilience.

Challenges to the digitisation of leisure

The digitalisation of leisure presented a variety of challenges that differed greatly between different parts of the sector. For example, while an orchestra could perform together via live streaming, players who relied on borrowed instruments were excluded. Those who were highly motivated continued their sport or hobby online, but those who were less engaged lost interest in the transition as the threshold for participation rose. (Kauppinen & Laine, 2022)

Several informants described how, after a day of online schooling or working, neither volunteers nor participants were motivated to take part in an online activity. Digital fatigue increased as the pandemic continued.

While several interviewees described how they could easily continue with their debates and statutory meetings online, they found that other features of face-to-face meetings were more difficult to recreate in a digital setting. One informant said:

‘Of course, it was possible to watch a film online and then organise a facilitated dialogue. But you wouldn’t get the chance to have a one-to-one conversation afterwards with friends or a youth leader or experience the spontaneous joy of meeting in person. Overall, it was much less inspiring than getting together in real life.’

Some youth organisations focusing on non-formal learning through interactive and fun activities struggled to attract participants. A volunteer in the cultural sector provided the following example:

‘We had to create online events and training sessions that were as appealing as films or TikTok videos because young people were really tired of doing activities on-line. For us as organisers, collecting memes, making videos and preparing fun, interactive exercises was very time-consuming and labour-intensive.’

Digitalisation reportedly worked better when groups already knew each other. One possible reason for this is that it is difficult to read body language and build new relationships in a digital space.

Across the sector, skills and competencies were insufficient to various degrees, resulting in an increased threshold for innovation within the youth and leisure sector. This issue was exacerbated by the existing knowledge gap between young people and youth workers. One positive example of how to address this issue can be found at Ungdommens Hus in the Norwegian municipality of Harstad. Here, young people played an active role in the digitalisation process, training staff in the use of digital media, teaching them how to set up Discord and Drawpile (an online drawing platform) and introducing them to podcasting.

There was also a lack of tools and equipment. For instance, many municipalities did not permit youth centres to use Discord servers due to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This presented a significant obstacle to the swift digitalisation of youth centres. The lack of granular control over data, concerns about data retention, and the problematic nature of obtaining consent from minors in a school setting mean that Discord is incompatible with the legal obligations of many municipalities.

However, one interviewee, an expert in the field, explained that it is possible to negotiate other terms and conditions with Discord to ensure consistency with municipal regulations.

Digitalisation – a threat or an opportunity?

Screen time surged during the pandemic and has remained high ever since. While acknowledging the risks of digitalisation, young people emphasise the important role that the digital arena plays in their lives. This is a fact that researchers, policymakers, and youth workers must not overlook.

The digital arena is an important social space for young people and has had a positive impact on various groups of young people during the pandemic. Online games and social media have been effective ways to cope with stress and boredom. The number of virtual encounters, such as voice and video calls, as well as multiplayer online games, has increased significantly. These offer a perceived sense of social support, reducing feelings of loneliness, boredom, and anger. In Ukraine, informants described WhatsApp groups as supportive platforms for youth workers, facilitating communication between them and young people.

Research is being conducted into the potential harmful effects on children and young people spending more time online. In Norway, a government-appointed ‘Screen Use Committee’ has been set up to examine the impact of screen time on young people’s leisure activities and well-being following the pandemic.

Research shows an association between high social media use and poorer mental health among adolescents. This is partly due to displacement of sleep and physical activity, as well as increased exposure to the pressure to participate, cyberbullying, and negative social comparisons. For instance, a youth worker describes how young people started to emulate influencers, which aggravated mental health issues among them. Several studies also support the displacement hypothesis, which highlights the fact that social media can take time away from activities that are known to promote well-being, such as leisure. (Kelly et al., 2019).

In Norway, an increase in gaming time was found to be linked to physical inactivity among young people. In Finland, there was an increase in gaming, particularly e-sports, alongside negative associations with daily physical activity. (Haug et al., 2022). One youth worker described how:

‘…young people lost two years of learning how to be together and instead learned how to be alone – online. Some continued this behaviour even after the pandemic.’

Although the digitalisation of the leisure provided vital continuity and social connection, which was reportedly appreciated by parents and young people, some challenges remained, especially for the more vulnerable:

‘We managed to get 85–90% of youth back to the club where I work after the pandemic. Unfortunately, we did lose a specific group of vulnerable kids struggling with stress, diagnoses of neuro divergence, and eating disorders. The increased time alone during lockdown may have exacerbated their conditions, giving them too much time to think. We also noted how some more introverted youth emerged with the on-line activities and some now prefer this to physical action and real-life meetings.’

Gaming culture can be toxic. However, there are also initiatives that focus on promoting positive gaming practices and providing guidance. The Safer Internet Centre is one such European initiative. Some youth centres, such as Helset in Norway, and youth organisations, such as SVEROK, Sweden work to raise the profile of gaming and create safe, inclusive online communities. These platforms offer access to supportive adults and leaders, as well as community-building and participatory, non-formal learning.

These examples demonstrate how organised, low-pressure online activities can foster a positive environment and a sense of digital togetherness, positively impacting well-being. (Bakken, 2020)

During and in the aftermath of the pandemic, public debate raised concerns based on the perception that youth work should be face-to-face primarily. (Utbildningsstyrelsen, 2025).

However, the digital youth work survey, conducted by Verke in Finland (2021), shows that by the end of the pandemic, 51% of youth workers considered interacting in digital environments to be as real as face-to-face encounters. One digital youth worker described how youth workers are present in chat rooms and activity rooms, just as they would be in real life:

‘We talk with the young people while we do an activity together and make sure to show that we see them.’

One other digital youth worker added:

‘Youth workers are present in on-line chat rooms and activity rooms, just as they would be in real life.’

For young people with disabilities, or for those who found it difficult to participate in physical activities for other reasons prior to the pandemic, digital solutions presented a new opportunity. A large-scale survey in Norway revealed that many young disabled people felt that they finally had the necessary adaptations to participate socially or follow lessons at school, thanks to increased digital technology use. This included online events and cultural experiences that enabled them to interact with others on an equal basis. (Nordic Welfare Centre, 2023).

One informant shared that the highly digitalised youth, who had previously experienced social exclusion in physical settings, were suddenly able to participate on equal terms.

For some, the threshold for sharing with a youth worker or other trusted adult online was also lowered, as digital forums allow for a degree of anonymity. (Valkenburg & Peter, 2011).

In conclusion, digital options provided adequate leisure activities and managed to reach some new groups of young people. However, they failed to fully compensate for the long-term loss of structured, semi-structured, and spontaneous physical activities, as well as the social interaction and guidance these activities provide. In particular, it was challenging to provide resilience factors such as togetherness and low-threshold inclusion. Research on Nordic teenagers indicates that robust offline social support (i.e., physical interaction) from multiple social networks (e.g., family, friends, teachers, and classmates) is most conducive to low levels of psychosomatic distress and the least problematic use of social media. (Gustafsson et al., 2025).

One interviewee stressed that, without digitalisation, young people’s access to social interaction would have been extremely limited during the pandemic. He stated:

‘It is important for adults to be careful when criticising, as our fears may be unfounded. During a crisis such as the pandemic, if adults discourage and hinder young people from meeting digitally, they risk depriving them of one of the few opportunities they have to interact outside of school.’

The interviewee then added:

‘We should remember that, while we must be aware of the risks connected to digital youth work, it is not necessarily bad. It is a source of empowerment and provides opportunities to learn and interact. Digital platforms are meeting spaces. They become what we make of them.’

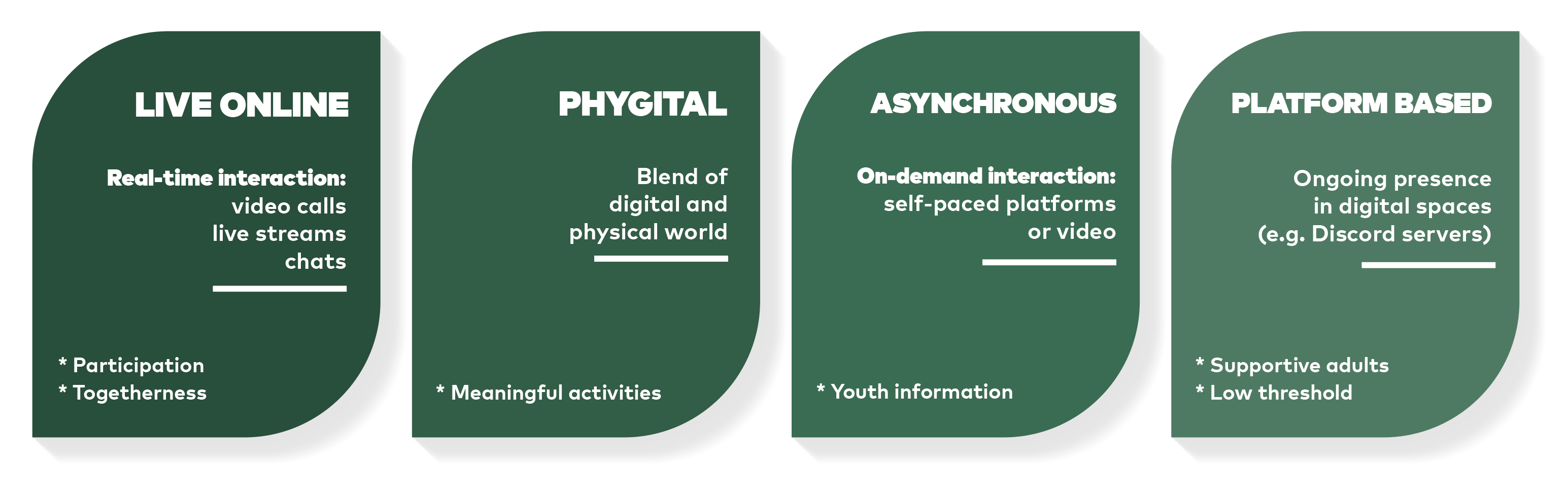

Figure 3.2 illustrates the four formats of digital youth work that were used during the pandemic. The format used for a given activity or method influenced how the well-being and resilience of young people was strengthened. Based on the examples identified in this chapter, the figure indicates the format particularly associated with a certain resilience factor. The figure suggests that resilience can be developed in digital environments through careful, evidence-based planning and development of digital youth work formats and methods.

Figure 3.2: Formats of digital work that were used primarily during the COVID-19 pandemic period, and their potential to build resilience in young people.

3.2 Relocation to outdoor and/or larger venues

Moving outdoors

Across Finland, Norway, and Sweden, there was a notable increase in outdoor recreation. This included more people walking in local areas, hiking, cycling, and even staying outdoors overnight. Young people were particularly active in this shift. (Statistisk sentralbyrå, Norway 2021; Gustafsson et al.,2025).

In Sweden, sports and outdoor activities were permitted to continue under safe conditions. Many clubs and training establishments, including gyms and yoga studios, moved their activities outdoors to places like parks and forests. New temporary walking and running groups were also formed. (Norberg, Andersson, & Hedenborg, 2022)

Also, Norway saw a significant increase in the use of nature as a social meeting place, particularly among young people. (Norsk Friluftsliv, 2021)

In interviews, some representatives of leisure organisations said that they had coped well during the pandemic by making minor adaptations to their activities and moving them outdoors. One such example is provided below, by a representative of a sports association in Åland.

‘We made short films showing what you could do at home, but we soon felt the need to train together and received requests from members to do so, so we moved outside. We rented a container for our equipment, placed it in a field, and relocated some of our activities there. We brought out benches, barriers, and so on, and I must say we were able to continue reasonably well. It wasn’t exactly the same as being indoors, but we managed to continue training. The municipality supported us by waiving the rent for our halls and the outdoor training area with artificial turf. Outdoor training became popular, which was great, but of course it was only a temporary solution. We could only do this in spring and summer.’

Whenever possible, youth centres relocated some of their activities outdoors. While some interviewees emphasised that outdoor youth work is possible even during the cold and rainy months, others were less convinced. Some centres organised ‘phygital’ activities, in which young people would go outside and do something physical before sharing the results with the group online. These activities could include sledging, building a snowman, or playing an online version of bingo where participants had to find items around their homes.

Challenges to outdoor adaptations

The adaptation came with its own set of challenges. Many sports can easily be played outside, but music teachers described the difficulty of playing an instrument outdoors in winter. In Norway, outdoor gatherings were sometimes prohibited or limited to three people. Some organisations also mentioned conflicts arising from the high demand for green spaces.

Requirements relating to outdoor infrastructure varied greatly within the leisure sector. Several interviewees emphasised the importance of having a roof, lighting, and electricity, as these would enable a variety of activities to go ahead regardless of the weather. However, there are no examples of municipalities providing these amenities.

Several interviewees highlighted the missed opportunity to establish outdoor leisure hubs where young people could gather safely. The latter was a recurring request from young people during the pandemic.

Instead, young people gathered in public spaces such as shopping centres, playgrounds, and streets. This sometimes resulted in conflicts, leading to the stigmatisation of young people as ‘rule breakers’. Furthermore, as ordinary citizens withdrew from the streets, outdoor spaces became unsafe for young people. In urban areas in particular, young people were increasingly exposed to adults with mental health problems or substance abuse issues, as there were no safe places to enjoy their leisure time. (Kauppinen & Laine, 2022)

One interviewee gave the example of an outdoor drama performance called Gäng (Gang), created in collaboration between the Finnish National Theatre and Digiloo, in Helsinki. Young actors guided audiences through the city centre, using audio to share their perspectives on the urban environment. The aim was to challenge negative public perceptions and explore young people’s experiences of urban spaces.

Access to schools and larger venues

During the pandemic, sports halls and other large venues were closed for the leisure sector. This made it difficult for youth centres and leisure organisations to find premises where the restrictions on numbers and social distancing could be adhered to. A representative of a cultural organisation said:

‘The municipality told us to carry on as before, but the venues were closed, and no alternatives were offered.’

Some interviewees cited the use of school premises for leisure activities in the afternoon or during evenings as a positive example of creating low-threshold activities. These efforts aimed to prevent infection spreading by limiting social interaction during free time to smaller groups or cohorts who were already meeting during the school day. The use of school premises for leisure activities after school is in line with the ‘Finnish model’. It should be mentioned here that the model was not an adjustment made as a response to the pandemic. It prescribes, among other things, leisure activities to be primarily organised in connection with the school day, often on school premises or nearby. This makes hobbies easily accessible and convenient for pupils, eliminating the need for separate transportation or complex logistics for parents.

As an example of good practice, a Swedish respondent mentioned the very popular night-time soccer arranged by local youth volunteers in a school sports hall in Tensta, Stockholm, which is considered a high-risk area.

3.3 Reduced group sizes and preregistration

Restrictions on group size meant that many hobby and youth organisations had to reduce the number of participants in their activities. While this allowed them to continue working, it presented several challenges.

Due to a lack of large premises that could accommodate several small groups of young people while guaranteeing safe distancing, hobby organisers were forced to reduce group sizes. As the number of youth leaders remained unchanged, this often meant that the time allocated for the activity had to be reduced. This led to a loss of many proactive, resilience-building factors, such as interaction with peers and youth leaders, and meant that the focus shifted solely to the activity itself.

Activities that would usually be open to all, such as those in youth centres or after-school leisure facilities, now required registration. This made participation more difficult, particularly when parental consent was required for registration. Several informants therefore requested a cohort structure, whereby the same young people could meet regularly without pre-registration. These groups could be school classes or hobby groups, for example.

3.4 Adaptations of roles and responsibilities

Umbrella organisations as crisis response coordinators

Umbrella organisations, such as municipal youth work organisations, national youth councils, and sector-specific groups (for instance, those for young disabled people), played a vital role in ensuring that young people continued to have access to leisure activities. A representative of one of the youth umbrella organisations narrated:

‘We evolved into a supportive hotline for local organisations. We translated the rules and provided counselling to try to reduce insecurity and stress. Gradually, even parents and young people began contacting us directly for immediate advice.’

The new roles assumed by the umbrella organisations included:

Explaining rules and safety guidelines. Providing sector-specific ‘translation’ of the rules and restrictions, and of how to ensure activities are safe.

Keeping policies and safety advice up to date , as rules changed.

Running a support hotline to answer questions from associations, coaches, trainers, etc. about regulations.

Sharing feedback from the ground, feeding back experiences and needs to policymakers.

Offering training and learning materials , such as how to work with young people online.

Creating spaces for youth workers and volunteers to support each other and exchange of experiences.

Managing funding , including handling applications for, and distribution of, funds.

During the pandemic, umbrella organisations pooled resources, reducing the need for various stakeholders in the youth and leisure sector to duplicate work or ‘reinvent the wheel’. For example, Ungdom og Fritid, a national, non-profit organisation which organises over 700 youth clubs in Norway, funded a digital team to provide training and support to all municipalities, rather than each one developing these capabilities independently.

Umbrella organisations also played a crucial role in supporting isolated professionals. In Ukraine, for instance, a youth work umbrella organisation emphasised the importance of supporting youth workers in rural areas. These workers often operate alone under high levels of stress, so the organisation provides them with the backing of a sector-specific body with knowledge of their field of work. This example illustrates a broader challenge faced by small, local organisations across Europe, limited opportunities for peer learning as well as lack of resources to access support mechanisms, such as funding programmes and educational materials.

Interviewees also provided examples of how umbrella organisations supported decision-makers. One interviewee representing an umbrella organisation said:

‘We had close and constructive dialogue with the authorities, both nationally and locally. We were able to report on the needs of our members, both large and small organisations. We felt that we were being heard and that efforts were being made to enable maximum participation.’

While these role adaptations demonstrate the sector’s resilience, they also highlight its underlying vulnerabilities. Youth umbrella organisations explained that their influence relied on pre-existing personal contacts rather than formal channels. Informants recount that, when invited to contribute, the format was often incompatible with the nature of the voluntary sector. Sometimes, they were given just a couple of hours to provide feedback, preventing them from consulting their member organisations.

The valuable assets – human resources and relatively stable funding – that major youth umbrella organisations had prior to the pandemic enabled them to take on new roles and respond readily as the crisis emerged, when combined with a resolute prioritisation as the crisis evolved.

Adaptation of roles within the leisure sector

An interviewee representing a volunteering umbrella organisation said:

‘Organisations can complement the public sector in important ways. For example, they have a different level of trust and understanding of different groups than the public sector does.’

A variety of tasks and responsibilities were taken on by civil society organisations, which identified a broad range of needs within society. Several civil society organisations in the Nordic countries stepped up to provide crucial psychological support and safe spaces for young people, often through hotlines and online services. Save the Children Norway, for example, set up a supportive hotline staffed by young volunteers to provide emotional support to children and young people. Existing hotlines increased their operating hours and contributed to the protection of children and young people by providing reports on mental health issues affecting this age group.

The example also illustrates how opportunities of volunteering can be created through crisis response, providing young people with a sense of agency and purpose during a crisis that had impacted their lives. Another example of a consious strategy to strengthen youth by volunteering during the pandemic is the special badge introduced by the Scouts during the pandemic. It encouraged scouts to engage with the community and take action

This provided young people with volunteering opportunities, giving them a sense of agency and purpose during a crisis that had impacted their lives. Another example is the ‘badge’ introduced by the Scouts to encourage their members to engage with the community and respond to the pandemic.

Throughout the study, informants who had experienced crises other than the pandemic offered valuable insights into how municipal youth services could adapt by taking on new roles and responsibilities to promote the well-being of young people during times of crisis. For example, after the volcanic eruption that led to the evacuation of the entire town of Grindavík in Iceland, the decision was made to relocate the youth centre with the evacuees to encourage togetherness and provide a safe space during the transition period while they settled into their new surroundings.

Similarly, youth centres in Ukraine help young internally displaced persons (IDPs) to make new friends and find a sense of community. As part of the response to the war crisis, they help IDPs find places to live and work, as well as volunteering opportunities. They even help IDPs develop the hard skills needed for employment and offer university students internships, as securing placements has proven challenging for the higher education system, which is now entirely online.

A representative of a Ukrainian youth organisation explained how they had become a resource centre for the entire municipality, not just young people. She asked:

‘Who else is accessible at weekends and in the evenings? Who has the skills to be one hundred per cent adaptable and flexible? Who has the competence to coordinate a thousand volunteers?’ Several informants identified the flexibility of the youth and leisure sector as the most important factor for successfully taking on new roles.’

A municipal youth work manager explained,

‘The youth and leisure sector has a tradition of doing things flexibly. We are accustomed to adapting to the preferences of young people, who live in a state of constant change. We can take advantage of this.’

Youth information

In a crisis, access to clear, accessible, and youth-friendly information is essential for many aspects of young people’s lives, including crisis-related matters and leisure activities. Several informants emphasised the need for information, emotional support, and youth services during crisis – and that these things are closely interlinked. A lack of appropriate information can create barriers to participation and feed fear and anxiety. (Barnens Rätt i Samhället, 2021)

A report from the Danish organisation for children’s rights, Børns Vilkår, describes how the COVID-19 pandemic created a new social context that was difficult to navigate without adequate information. Children and young people, for instance, reported being teased by their peers for either adhering too strictly or too loosely to the restrictions.

Several informants also described how challenging it was for young people to find out which leisure activities and spaces were available, given that restrictions were constantly changing. In Sønderborg, Denmark, young people developed recommendations for the municipality, one of which was clear and easy-to-use communication about the municipality’s sports and cultural opportunities for young people.

While official information often came from national health authorities and traditional media, youth organisations, civil society groups, and youth workers became important intermediaries. They translated complex restrictions and guidelines into understandable formats and distributed them through their established networks and also spread information about helplines and mental health care. (NOVA, 2021)

The Finnish model of youth information is a prime example of how structured, empowering, and participatory youth information services can be delivered – something that has not been replicated in other Nordic countries. Thanks to its solid legal mandate, robust digital infrastructure, trained professionals, and national coordination, the model provided a robust foundation for youth information work during the pandemic. Koordinaatti, the Finnish National Centre of Expertise for Youth Information, operated between 2006 and 2024 and played a pivotal role in maintaining and developing this model. During the pandemic, Koordinaatti acted as a national hub for youth information professionals, providing them with up-to-date, verified information about the virus and offering support.

Koordinaatti also ran Nuortenelämä.fi, a national youth information platform featuring a national chat and a Questions & Answers service staffed by dozens of professionals. Information about hotlines and chat channels was shared on social media to reach young people. Influencers were also enlisted to help spread the word. Several interviewees and respondents emphasised the latter as an innovative and effective measure.

Across the Nordic region, civil society organisations and municipal youth workers played a key role in leveraging their platforms and expertise in youth language, media, and communication tools. They often had direct contact with vulnerable young people and immigrant communities who might have faced greater challenges in accessing or understanding official information due to language barriers or digital exclusion. These organisations were therefore crucial channels through which public authorities could effectively reach young people, and they also provided the authorities with valuable feedback to help them tailor their communication strategies. (Nordic Welfare Centre, 2022) One youth worker explained:

‘We would talk about the vaccination and address any concerns the young person had. Sometimes, we would even accompany them to get their shot.’

Another youth work expert explained that the leisure sector also played an important role in providing a space for reflection:

‘At the start of the pandemic, there was a lot of uncertainty and many scary things for young people to deal with. Our most important role is to listen to people’s concerns, provide emotional support, and offer media criticism. Now, more than ever.’

Both civil society and municipal youth workers rely heavily on state-level resources to provide young people with adequate information and counselling on a large scale. An interviewee representing a youth work umbrella organisation concluded:

‘Youth information work is a very important role. We tried but received no support or structure. We really need this support to fulfil our important role.’

3.5 Detached youth work

A proven method of maintaining a presence and accessibility for youth workers is to use detached youth work to target young people not participating in the leisure sector. This approach proved particularly useful during the pandemic. As described by one informant:

‘Some municipalities increased their work with young people as youth centres closed, but there was no general or systematic strategy for outreach work with young people.’

Even greater efforts were made during the pandemic to reach out to young people in Helsinki, Finland, where detached youth work had been ongoing for decades. One interviewee recounted:

‘Youth street workers found young people wherever they were – in train stations, shopping malls, or at outdoor parties – and offered them support and a listening ear.’

According to one interviewee, the number of street-based youth workers in Danish Biborg increased from zero to 14, four of whom remained after the pandemic.

While these municipalities have increased the number of youth workers, interviewees indicated that detached youth work has not been implemented on a large enough scale to benefit young people in general. This approach requires more resources given its reliance on one-to-one contact, yet few additional resources have been provided. Some youth workers also mentioned that young people were not to be found outdoors and speculated that this was due to restrictions or overprotective parents trying to keep their children at home.

Detached youth work is a valuable source of information for the effective organisation of youth-related policies and activities, particularly in a crisis. A local youth police officer said:

‘Municipal youth workers know exactly how young people feel, what concerns and interests them as a group.’

The officer then added:

‘They have their finger on the pulse like no one else.’

A youth work director explained that, unlike adults who try to control them, youth workers can accompany young people wherever they go and be accepted as supportive adults:

‘This knowledge about their whereabouts, together with the data we collect, is a great asset in a crisis.’

A detached youth worker described the importance of reaching out to young people and meeting them where they are, even in the post-pandemic era:

‘Many young people have given up their hobbies, and their patience levels are low. We support their participation in the leisure sector by motivating them and encouraging them to continue. We also encourage them to contact mental health services, help them stay on the waiting list, and accompany them to appointments.’