Legalized cannabis: Quo vadis, Massachusetts?

DrugsMatilda Hellman, Editor-in-chief, Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs Published 8 Nov 2018

Matilda Hellman, Editor-in-chief, Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs Published 8 Nov 2018

The seminar “So We Legalize Marijuana. Then What Happens?” was arranged in Boston in October 2018 with the aim of unpacking the consequences of the legalization of recreational cannabis use.

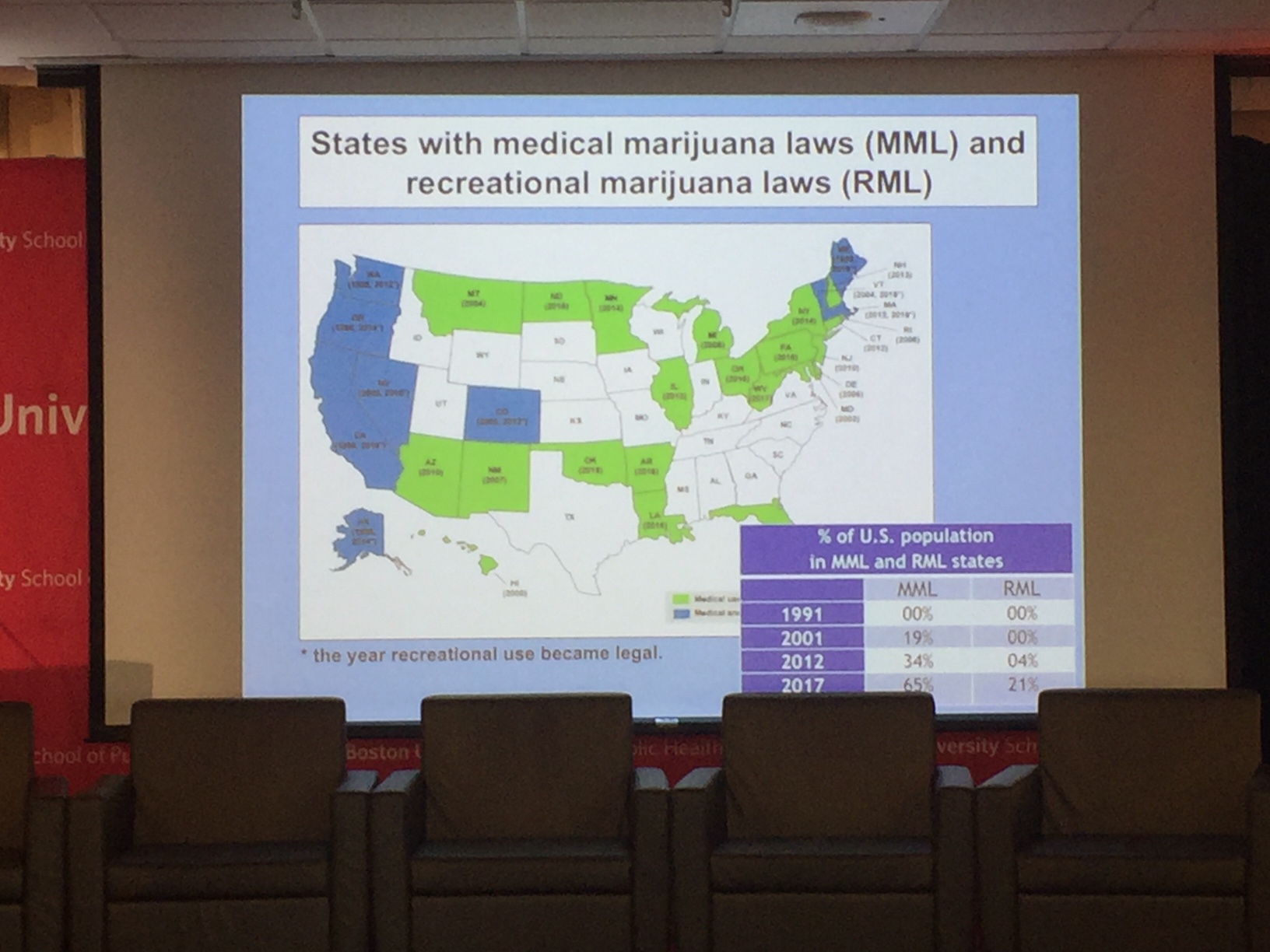

This is not a minor question in current American society: 20 percent of the US citizens live in states where recreational cannabis business and use is legal. The first retail licenses for recreational marijuana use are being issued in Massachusetts, a state in the New England region of the United States, with almost 6.9 million inhabitants. Entrepreneur Keith Cooper’s medical cannabis company Revolutionary Clinics (RC) is ready to jump on the wagon of the evolving recreational marijuana industry. With a background in the tech industry, Cooper describes the crucial impetus for engaging in the cannabis industry with the realization that it is likely to become “the biggest and fastest growing industry in the history of our country.” Cooper was one of four speakers at the seminar hosted by the Boston University School of Public Health on October 25, 2018. The contextual perspectives of the seminar was the result of a variety of angles.

Neuroscientist Marisa Silveri was first out. Silveri, who conducts work on neurobiological developments in addiction, explained the ways in which brain scans with stimulus provide a window into brain development. Adolescents’ developing brains are of special interest in research into correlations between personality characteristics or depression, on the one hand, and the consequences of cannabis use, on the other.

“The brain is not adult until the mid-20s,” established Silveri, and referred especially to the frontal lobe’s abilities to make decisions.

The effect of cannabis on short-term reward systems, cognitive skills, and memory is evidence that needs to be taken into consideration in addition to knowledge on self-reported prevalence and harm of cannabis among youngsters.

Nevertheless, and rather surprisingly, the legalization of both medical and recreational use of cannabis seems to coincide with a declining trend in youth substance use. This was one of the main points highlighted by Columbia University epidemiologist Deborah Hasin in her exploration of stats stemming from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

Increasingly, among both American adults and adolescents, cannabis is being seen as not harmful, but rather riskless and safe. According to Hasin, this could be interpreted as part of a normalization of cannabis as a substance. This is worrying, especially as the prevalence of cannabis use disorders among adults has doubled in the ten years between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013.

Hasin’s work points out several simultaneous trends: while the risk of cannabis use disorder is generally higher today than before, the numbers suggest that neither medical nor recreational legalization correlates with a subsequent increased use of cannabis. This is the case at least among youngsters in the states that have gone through the legalization process.

As in the cases of alcohol use and binge drinking, the trend curve of cannabis use among American youth has recently taken a downward turn. At the same time, mental health problems, suicide rates, and depression diagnoses are becoming much more common among teenagers:

“Adolescents may to a less degree be out attending parties which have traditionally involved substance use possibilities. They may be sitting home in their rooms alone in front of their screens,” speculates Hasin. By doing so she is echoing one of the most popular theories on why young people’s substance use is decreasing in many parts of the Western world.

The correlation between the decrease in youth substance use and less face-to-face “hanging out” with peers, on the one hand, and increased mental ill health, on the other, may be yet another proof of the well-documented social rationale of substance use, and particularly of youth substance use. This is a question that qualitative researchers have been busy unfolding for several decades. A trend that might explain the increase in cannabis use disorders despite the general decrease in use may, in turn, be the increasing general fixation on diagnosis in health care systems.

When it comes to the relationship between the decreasing youth use of substances and the legalization of cannabis, these events might just be coincidental. Coincidence or not, it was not expected by the epidemiologists who embarked on the question of how both medical and recreational cannabis legalization politics would affect the prevalence in cannabis use. Only in adults over 26 years has there been an increase in cannabis use after legalization. This speaks volumes of the use patterns and the justification of use by the consumers that the legalization laws (medical and recreational) are serving. However, this needs to be investigated more closely by both quantitative and qualitative means in order to be properly understood.

The last presenter of the event was Beau Kilmer, a cannabis policy expert from the RAND Drug Policy Research Center. Kilmer connected the discussion to a principle level of systemic alternatives of regulation. From a list of 12 considerations Kilmer chose to speak about supply models and their profit alternatives as well as price considerations.

Kilmer raised the question of the share of the profits being made from heavy users of “vices” such as alcohol and gambling – a question that must be asked also in the case of cannabis control. In fact, identical questions to the classic ones raised in alcohol policy research regarding price regulation and availability control, and their relationships with public health, now need to be studied as to cannabis markets.

A challenging circumstance is the growing wholesale and retail cannabis industry, and the many markets that can be targeted through future potential dissemination channels such as Amazon. Another challenge is that customers can be enticed by new types of marketing or youth-appealing product variants such as sweet bakery goods or cannabis gummy bears.

The question marks on cannabis legalization concern especially taxation. As Kilmer pointed out, nobody really knows how to tax cannabis. Another question concerns minimal price levels and implementations. In Canada, the government plays a key role in the setting of prices, in contrast to the US, where markets are available for (highly controlled) private enterprises in the same manner as for alcohol producers. When markets are rather independent at the outset, jurisdictions need to adjust policies as they go along, and the proof burden of such benefits, which are costly to produce, must concur with the political argumentation for restriction.

The decision of the outset level of control measures and the role of the government is hugely relevant in the ways in which control over cannabis as a product unfolds in any given state. Referring to liberalizing control, Kilmer employed the metaphor that when the genie is out of the bottle, it is hard to squeeze it back inside. It is indeed well established that it is more difficult to take control measures in order to fix liberal control policies than to liberalize markets that are controlled. This is certainly a crucial question that societies legalizing cannabis must take into consideration, especially a liberalist capitalist country such as the United States.

The seminar’s end discussion, moderated by addiction medicine profile Richard Saitz (Boston University), summarized some contextual approaches to cannabis legalization. Factors to consider include the changing use patterns, the evidence on harm from cannabis in terms of increased depression, respiratory illness from smoked cannabis, and lower cognitive skills. On the societal level a negative impact of legalization has been shown to include an increased prevalence of Driving Under Influence (DUI).

Yet another important approach to understanding the bigger picture is to take into consideration the policies in areas such as pharmaceutical opioids, alcohol, tobacco, and gambling. These markets not only overlap and react to one another, but their regulation principles must involve the ways in which the products’ recreational use lead to ill public health and societal and economic costs.

It is up to the individual jurisdictions or governments to decide upon and implement a clear principle agenda in the cannabis question, based on a weighing between collective control benefits and the consumers’ individual freedom. Only now when a considerable number of societies are starting to legalize the product can we start making comparisons of different models to regulate this substance.

Massachusetts is the latest in a row of jurisdictions that has to deal with a whole new set of of governance issues due to legalized cannabis. Should entrepreneurs such as Keith Cooper be allowed to make money on a substance that carries so many problems? Should it be seen as replacing other, more harmful vices, or should the state budget be compensated for the societal costs? The seminar arranged by Boston University was a first step toward unfolding these questions so relevant for future governance.

About the writer:

Matilda Hellman is editor-in-chief for Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs (NAD). In the fall of 2018, she works as a visiting scholar at Harvard University and lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.