Governance – a theoretical introduction |

|---|

Cross-sectoral collaboration in digital health and social service provisions

The Norwegian Centre for E-health Research has been invited to contribute with a theoretical framework to the project report Integrated healthcare and care through distance spanning solutions, a building block for a sustainable Nordic region 2021-2024 (iHAC).

The project’s main objective has been to map the examples of integrated healthcare and social care on a regional scale. This report presents five regional models of collaboration within the healthcare and care sector in, Denmark, Iceland, Finland, Norway and Sweden. What all these model regions have in common is collaboration across healthcare sectors and institutions.

Most of the collaboration models also cover several municipalities within a geographical region. Because of the countries’ different ways of organizing the healthcare and care services, the regional models will differ to a certain extent. However, building on a similar welfare state model and a well-developed public sector, the Nordic countries do have much in common, and thus it was contended that some degree of comparison is warranted.

As will be shown later in the report, the contributing regions have reached very different stages of service implementation: The regions in Denmark, Norway and Sweden have established organizations, routines, and services. The Finnish and Icelandic regions, on the other hand, are still in the project development stage and are planning the introduction of their services. Because of this, the choice was made to not range the regions based on our theoretical framework, but instead, see how each region incorporates elements of governance. The preceding project, Healthcare and care through distance spanning solutions (VOPD), contributed with knowledge on developing and implementing digital service models in healthcare and social care services. The acquired knowledge gives direction on how digital services can be adopted in sparsely populated areas.

A result of this project was, among others, an English translation of the Norwegian-developed Roadmap for Service Innovation[1]Add in a box: Several models and frameworks for the adoption of e-health exist. One example is the Non-adoption, Abandonment, Scaleup, Spread and Sustainability framework (Greenhalgh, 2017)[2], and another is the Normalization Process Theory (May et. Al, 2018)[3].

Five examples of cross-sectoral collaboration

In this report, five examples of cross-sectoral collaboration within health care and social care in the Nordic countries will be presented.

- Region of Southern Denmark, Denmark

- Päijät-Häme welfare district, Finland

- Fjallabyggd Municipality – Northeast region, Iceland

- Regional Coordination Group (RCG) for e-health and welfare technology in Agder, Norway

- Tiohundra Norrtälje, Sweden

The report aims to show how the different regions are organized, what they have in common, and what differs. To help the reader observe and understand these similarities and differences, a theoretical framework on governance is presented, based on Røiseland and Vabo (2016)[BA1] . The governance framework has been found useful when looking at the complexity that characterizes the organization and adoption of e-health and distance-spanning solutions: Several actors representing the primary health care and specialist health care services, national authorities, policy, the law, non-governmental organizations, the industry etc. The presentation of this framework is illustrated using examples from the empirical material that will be presented later in the report. These examples are used mainly for pedagogical value, and our presentation is thus not intended as an exhaustive analysis.

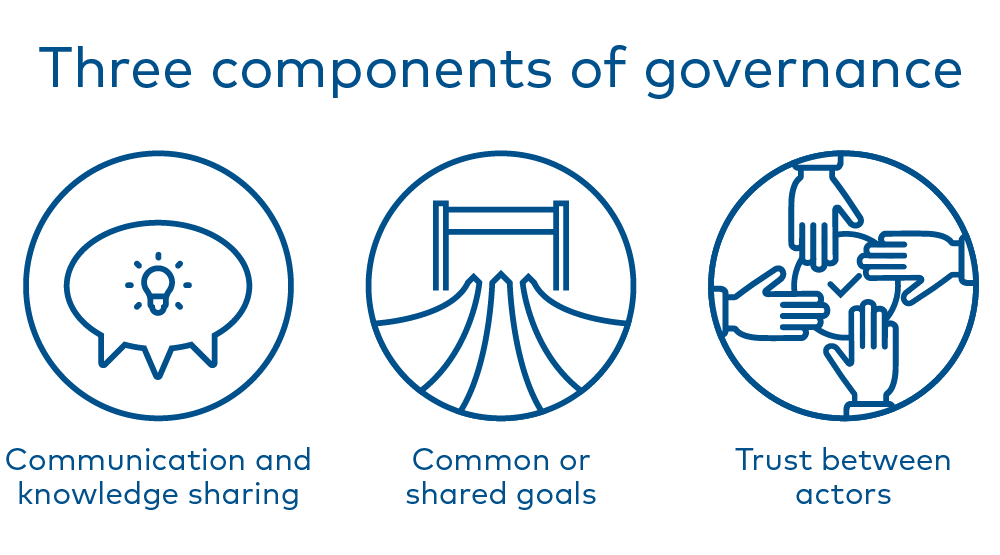

A questionnaire to the regions was also designed with Røiseland and Vabo’s (2016) framework in mind, and in particular the three characteristics, they consider necessary for governance to succeed:

- knowledge-sharing and communication

- common goals

- trust.

Methodology

The basis of this report is, as mentioned above a questionnaire which was sent out to regions throughout the five Nordic countries. The chosen regions were selected by the steering group of the project, and the survey was distributed by the project management to key persons in the chosen regions.

This questionnaire was developed based on the objectives of the iHAC-project, as well as on the components of the governance framework (Røiseland & Vabo, 2016). This theoretical framework was chosen because the healthcare sector is characterized by complex cross-sectoral problem solving and high demands for coordination and cooperation, and this dynamic has been fruitfully analysed by other researchers using governance-related terms and literature. Additionally, the three components that will be discussed (communication, shared goals, and trust) reflect how actors in health care view their own challenges. The governance framework also helps us understand the complexity of the health care sector. The end-users receiving services from the healthcare and social care services have complex needs and the number of users with complicated challenges and with complex needs will continue to rise each year. The challenges that arise when several institutions and service organizations are involved to cater to these users’ needs have already been mentioned. The solution to this challenge in all Nordic countries is increased coordinated care and information sharing across sectors, rather than fragmented services. National governing documents and white papers, therefore, highlight the need for coordinated care and increased information (sharing) to ensure holistic patient pathways.

The three characteristics of governance which will be discussed show some of the challenges the social and healthcare sector faces, and whilst Røiseland and Vabo (2016) don’t give us all the answers to the challenges the social and healthcare services are facing, they can still be used as a tool to operate with.

In addition to the questionnaire, the five regions were asked to give some general information, e.g., network members and when the regional network collaboration was established. Some questions were also open-ended, giving the respondents the opportunity to answer more fully. This questionnaire and the descriptions of the regions in the report were later used as a basis for interviews with each of the regions, conducted by The Nordic Welfare Centre.

Whilst the questionnaire did have some methodological weaknesses, these were compensated by the follow-up interviews. Here, questions were clarified, and representatives from the regions were able to expand on their previous answers. The issue of representation was present in the regions that evaluated themselves in the questionnaire – whilst some participants had discussed it broadly within their own network, others hadn’t. As such, their answers are based on their personal understanding of the questionnaire, which again may not represent the views of the whole region. However, it can also be added that the fact that the regions each answered differently can also be viewed as positive, as an insight that might otherwise have been overlooked was received.

What is governance?

Before looking at governance, it may be helpful to look at what it means to govern. According to Røiseland and Vabo (2016), governing consists of two things: Making decisions, and following through on these decisions, thus suggesting that governing is about affecting and changing society in a conscious and thought-out manner. The word “governance” itself is defined as “the actions or manner of governing” (p. 17).

Despite this seemingly simple definition, when one looks at how governance has been used in practice and described in the literature, there are many definitions to choose from. Therefore, it is also important to define what is meant when talking about governance as a theoretical framework[4]. Here, Røiseland and Vabo’s (2016) definition will be used:

“The non-hierarchical process whereby public and/or private actors and resources are coordinated and given a common direction and meaning” (p. 21).

Governance, thus defined, is non-hierarchical – as opposed to traditional bureaucratic steering, and oriented towards cooperation – as opposed to New Public Management. The text elaborates on this below.

Governance is both an analytical tool and a distinct approach to problem-solving. As an analytical tool, the governance framework may help us take/understand the perspective of autonomous actors put in a situation where they need to work together, as it can help describe and understand the processes parties go through – how their goals are formulated, negotiated, and possibly achieved, and why there are challenges.

As a practical approach to problem-solving, governance is relevant for example when e-health solutions are to be implemented across administrative levels, and hierarchical management models (where directives are given, and each party follows up) aren’t necessarily suitable. Therefore, one turns to governance instead. This can be seen in the Nordic countries, where municipalities have a much more autonomous role than hospitals. Even though hospitals are organized in a very hierarchical manner, to obtain coordinated care, other mechanisms and solutions are needed. Governance as a practical approach is also relevant in situations where steering according to New Public Management principles may be problematic, for example concerning issues where fragmentation and silo-organization prevail.

The building blocks of governance

Within the definition of governance, Røiseland and Vabo (2016) state that there are three specific characteristics that lie within their definition: The first of these is that the participants are mutually dependent on one another – as mentioned, they are trying to achieve something that can only be done together. These goals can only be achieved together due to their different resources, which can be things like expertise or local knowledge. Going back to the health care sector and the patients with complex needs; to obtain holistic patient pathways, all parties within the specialist and primary healthcare services must share information and work towards the same goals. After discharging the complex patient, the hospital depends on the general practitioner (GP) to follow up with the patient regularly, and the GP depends on the municipal home care services to follow the user daily. They should all ensure the prescribed medication is taken, that the correct food is eaten, and other special precautions are taken care of.

Discussions and agreements

Secondly, precisely because all participants are dependent on one another, this affects how decisions are made. It is important to note that governance, as Røiseland and Vabo (2016) define it, is only possible when all parties can discuss and potentially reach agreements. As such, normal modes of power, such as directives or commands may not work. If force is used, then there is a risk that other participants who contribute with important resources may pull out of the cooperation. This can potentially happen when there is too strong top-down governance involved. If, for example, the contributing parties are used to a non-hierarchical structure, too much leadership may cause friction. Too much strong top-down governance may also lead to the person in charge of cooperation being unable to use everyone’s knowledge effectively. The whole point of governance is, after all, to mobilize the involved parties´ unique expertise and initiative in complex problem-solving. It can safely be assumed that the governing authorities' knowledge and perspective on the given problem will be narrower than the sum of all the involved parties´ knowledge. Therefore, it is vital that the “governance of governance” is based on incentives, soft control, and leadership, instead of the tools that are traditionally used in the public domain (i.e., laws and rules) (Røiseland & Vabo 2016). Too strong steering, thus, can undo the purpose of governance, which is, after all, an increased ability to solve complex problems.

The element of negotiation can be seen in all contributing regions in this report: They have all developed fora and institutions to share information, discuss, and obtain agreements. This is visible, especially in the Norwegian Agder region where all parties also have signed cooperation agreements. Through this agreement, the parties have committed to collaborate and let the regional coordinating structure organize the health services. The parties also commit to working towards common goals.

Making it happen

The third and final characteristic is one that has already been mentioned: That governance is an attempt at following through on ideas and achieving something. This is closely related to the second characteristic, as it requires that activities are based on shared goals. As such, governance also involves the basic processes of an organization. This means that these shared goals and potential strategies must be planned out in advance, and activities need to be coordinated. The result of this is that parties who use governance as a way of leading will look quite similar to a formal organization, although the hierarchy will, of course, be a lot more relaxed than one would normally expect (Røiseland & Vabo, 2016).

The differences and connections between the three characteristics presented above, and the three characteristics that will soon be presented, is that the first three are what makes governance special, whilst the characteristics presented now are deemed vital if governance is to succeed.

Why governance?

Many of the problems facing the digitalization of healthcare are described as problems of cooperation and/or coordination. This is perhaps unsurprising, given the complexity of modern healthcare sectors, and the notorious difficulty of cooperation, both as an object of study and as practice. However, this also means that cooperation (or collective action) attracts the work of many scholars working on what criteria and components must be in place to make cooperation successful (Vik & Hjelseth, 2022).

For example, the implementation of welfare technology in municipalities may be seen as a cross-sectoral problem/challenge, involving many different actors in different sectors such as the economy, health care, politics, authorities, law, education, family, mass media, research, civil society/voluntary, sports etc. This means that the successful implementation of welfare technology is a cross-sectoral challenge that depends on cooperation for its solution. In addition, market-like steering through New Public Management often generates problems like fragmentation, so-called “silos” and reduced collective problem-solving capability, and the emergence of the governance framework is often seen as a response to this. Governance may thus also come to be expected and seen as a source of legitimacy for decision-makers.

Three problems and three solutions

The promise of governance as an approach to cross-sectoral problem solving may be seen in relation to three distinct problems, each of which is complemented by a distinct solution.

As indicated above, the starting point is always a network of interdependent and more or less equal actors trying to solve a complex problem together. Whilst all actors have their own perspective on and knowledge about the problem, no one has the full picture. Moreover, the different actors each bring different goals to the table, and in absence of hierarchy, it is not obvious whose goals should apply. Lastly, the lack of hierarchy also leads us to the question of how to ensure adherence to these decisions.

Røiseland and Vabo (2016), argue there are three solutions to these problems: 1) the information problem should be addressed by ensuring (through leadership, appropriate channels for) communication and knowledge sharing, 2) the problem of conflicting goals should be addressed by establishing common or shared goals, and 3) the problem of adherence should be addressed through establishing trust between actors.

Communication and knowledge sharing

Communication is a vital aspect of governance, simply because there would be no governance without it. If different stakeholders are going to agree or disagree on things, then actors working within a framework of governance need to be able to express their own views and have an opinion of other parties’ viewpoints. Sharing knowledge is also key here, as this makes it possible to understand what kind of questions are important to ask, what challenges may arise in the project, and help give an understanding if and when crises occur. The central point here is that one party needs to be able to convince the other through discussions and arguments and that these new ideas will lead to a change in what the other party believes is both desirable and possible within the cooperation. Røiseland and Vabo (2016) also point out that it is gaps of knowledge that make cooperation necessary in the first place, and that lack of communication is often a factor in why cooperation fails. One critical part of the patient pathway is the patient’s transfer between the service levels in the health care sector. Due to lack of communication and misunderstandings, complex patients are for example often hospitalized shortly after their discharge (Fredwall et al., 2020[5]), and unplanned hospital admissions for older people are a problem for health systems internationally (Huntley et al., 2022[6]).

Indeed, the reason inter-organizational cooperation is established is that each organization wants to find solutions that they cannot solve alone. In the health care sector, the most natural example would be that of the patient, who is treated in both specialist and primary health care services. If the patient ends up in a hospital, then they are treated there before being discharged. However, they will still need to be followed up both by their GP and the municipal health care services. To ensure that the patient receives good treatment, it is vital that health care services on all levels communicate and share information, both about and with the patient.

Arenas for communication

Cooperation also represents a way of connecting different organizations together, leading to information and knowledge being both developed and shared (Røiseland & Vabo, 2016). As will be seen later in the report, all presented regional networks have structures or regular meetings and common arenas for communication and knowledge sharing. In the interviews, these meetings are mentioned as important arenas for sharing ideas and avoiding misunderstanding one another. One example is the Swedish network, who meets every Monday. During these meetings, all collaborating parties discuss both big and small issues. These regular meetings are important because all the parties are given the opportunity to raise and discuss issues important to them, thus avoiding misunderstandings and building trust. The Norwegian network has also spent a lot of time on developing the structures of the network, in which regular video meetings is one of several factors. Another practical example of both communication and knowledge would be South Denmark’s wound assessment platform. Even for Finland, who is still only in the project planning phase communication and knowledge sharing are important aspects of their KOHTI Ecosystem model.

On the other hand, the Icelandic network said in their interview that they were having trouble with their project, precisely because there were difficulties regarding information-sharing. Even though the legal framework in Iceland states that people should work together, and that health and social care are supposed to share, the network here stated that there wasn’t a tradition for sharing. Indeed, people are more preoccupied with not sharing than finding a solution as to how to share.

Common goals – formative function towards continuity

Common goals are considered important because they have a formative function – this means that they shape both what the contents of the cooperation include, and the relationship between the participants and how they cooperate with one another. In terms of results, an important question to ask is “Whose goals should guide the cooperation?” (Røiseland & Vabo, 2016). In its extreme consequence, this can be seen in the financing systems of the health care services. Both the primary health care services and the specialist health care services are governed by financial results. When remote digital care as a service is introduced, this can be costly for the municipality because the patients are discharged from the hospital at an early stage and need close following-up from the home-care services, while the hospital saves on it. Whose financial targets should one then relate to? The same goes for the specialist health care services being diagnosis-oriented, hospitals as a general think and treat patients based on their specific diagnosis, whereas the home care service in the municipality looks at the patient as a whole – can they for example live at home? If they fall and hurt themselves, why did the fall happen? Is the patient eating, why or why not?

Within the context of the five chosen regions, we can say that RCG Agder has the common goal of following through on the Norwegian National Health and Hospital Plan, where the objective is to get the municipalities and hospitals to collaborate towards better continuity of care. In South Denmark, shared goals have also been important in relation to the “big why” question – citizens and health professionals alike must understand why the service is being implemented, and what the benefits will be.

Specific types of goals

Here, it might also be fruitful to make the distinction between three specific types of goals: Firstly, the goal of the cooperation, which gives an indication of what the participants wish to achieve together. Secondly, the goal of the different health care actors in the network – these are likely to emerge regardless of the cooperation and will express the expectations within the cooperation. In this case, it can be pointed out that the goal of the cooperation will be placed above the participating organization’s individual goals and vice versa. Finally, there are individual goals, which are related to the individual participant’s career and their personal preferences. This type is perhaps the least common, as individuals often serve as representatives for a head company or other representatives. Looking back to what has been presented earlier, having these different types of goals is a strength, as it allows all participants to make their voices heard. However, this can also be challenging: Because each party contributes with their specific expertise, it makes common goals harder to define in the first place. In a worst-case scenario, this can lead to conflict, and even when disagreements are solved, this is still a problem, as in some cases, it can mean that important things such as principles and scientific expertise are compromised or negotiated away (Røiseland & Vabo, 2016).

Establishing a common purpose and common goals is imperative in the specific field described in this report. Implementing digital service models in cross-sectoral fields, with autonomous actors characterized by a fragmented organizational approach is indeed challenging – no decision-maker at the very top level can enforce activities to happen. Thus, all the five regional networks presented in this report have developed common goals. The networks also use several approaches to anchor these goals among the participants of the network to ensure the ownership of policymakers’ top-level and middle managers, as well as end-users. Although working towards the same goal can be challenging, it is also an exercise the parties do together.

Trust – investment now will bear fruits tomorrow

The final component of governance is trust. Røiseland and Vabo (2016) write that trust in cooperation works as a response to the complexities of working in a network-like cooperation. Instead of having the hierarchical structures of an organization, one has trust instead. Trust is also an “assumption that the investment you make now will bear fruits in the future” (p. 80). Furthermore, trust is also the assumption and decision to believe that other parties will also work towards the same goal(s): For example, that the hospital won’t discharge the complex patient too early, but in such a condition that the prescribed remote monitoring will ensure the patient’s safety; that the GP will follow the prescribed medication list, and that the home care services, via telemedicine, ensures the patient actually takes their prescribed medicine. Trust is also involved when local politicians decide to purchase costly digital solutions because they think it will enable quality health services for their elderly, and when the municipal manager outsources ICT support services to a neighbouring or private vendor.

Trust as a common factor is highlighted as important by all the regional networks contributing to this report. However, it is clear to see that trust as an ideal is highlighted as imperative by the networks that have existed for several years. Trust was repeatedly mentioned as essential by all representatives from the Norwegian network. This network consists of both very small and large municipalities, and as such, all parties need to know that their contribution is important and that they will gain something by contributing. Here, the network continuously works together to develop and create the feeling of being part of a team, in order to create trust between all parties.

Trust will lead to results

Røiseland and Vabo (2016) highlight three advantages of having a high level of trust: Firstly, trust may reduce costs that appear throughout the cooperation, because of reduced transaction costs. This has been highlighted as important for Tiohundra Sweden. Secondly, trust consolidates the cooperation, and makes participants more willing to invest in this shared interest. Finally, trust between participants will lead to results, because, as has been mentioned before, knowledge will be shared, and all participants’ resources will be combined. These resources and knowledge will then be used in ways that increase the participants’ chances to solve problems and contribute to innovation.

One may also point out that whilst trust in itself isn’t negative, it can lead to vulnerability. There are many problems that can threaten and undermine it, and this can lead to challenges when cooperating. Trust is a crucial aspect of governance, and when it is broken, the possibility of solving problems together is drastically reduced. Despite these vulnerabilities, the process of building trust makes the parties’ expectations, and the risk and vulnerability affect one another in a positive circle where trust is built through positive experiences of cooperation.

Strengths of governance

Whilst there are many reasons why one should employ governance, one only has to look at the democratic aspect to see why it can be valuable. If one is to have a legitimate democratic government, this presumes that the government can meet the needs of the population and solve central societal issues. As Røiseland and Vabo (2016) note, Western societies have gone through massive changes in the past 20-30 years, and as such, society has become a lot more complex, and expectations have become higher. This in turn requires more complex services and solutions. This increased complexity means that it has become much harder for authorities alone to have an oversight of societal problems. Therefore, other actors’ perspectives need to be involved.

Because of the need for more complex solutions, figures of authority can’t just go out and interview the affected parties and get an overview this way, as both their problems and solutions will be too complex. This leads to a situation where the affected party’s autonomy needs to be kept intact and be considered equally valuable to authorities’ knowledge. As such, Røiseland and Vabo (ibid) believe that governance is “a completely necessary adaptation for the needs and problems that public authorities are expected to handle” (p. 36).

The need for cooperation is vital

As described earlier in this chapter, the social and healthcare sectors are known by both formal and informal expectations to engage in complex problems involving many more or less autonomous parts who must coordinate their efforts in order to produce an intended outcome. Therefore, the need for cooperation between all participants is vital. This shows exactly why governance is both a necessary and valuable mode of leadership – because it fills a need that public administration traditionally doesn’t fill (Røiseland & Vabo, 2016).

The change towards governance was a change that began already in the post-war period when public administration eventually became New Public Management in the 1980’s. In this period, the modern welfare state grew, and the belief in public management and public authorities to solve societal issues was strong in well-developed countries. In this period, governance happened through law-making and bureaucracy-made rules and guidelines. Here, the state was viewed as one unified actor, and the boundaries between public and private were well-defined. There was also a clear difference between politics and administration, and one had to differentiate between policy formulation and the implementation of politics – whilst politicians are expected to design politics, the bureaucracy’s job is to implement them (Røiseland & Vabo, 2016).

This way of thinking changed again in the 1970’s, when New Public Management was introduced. Here, the key difference is that New Public Management operates with the idea that there is no difference in what the public and private sectors represent, and the organization, management, and leadership are all general processes, and models that may be copied across the public/private order. However, what mostly ended up happening was an import from the private to the public sector, leading to the dismissal of public agencies. This in turn led to public management being more regulated, where politicians set out goals, and public businesses were responsible for achieving these goals within their allocated resources (Røiseland & Vabo, 2016).

As mentioned earlier, governance became popular around 1990. Of course, this doesn’t mean that governance completely replaced public administration and New Public Management, intended instead as a supplement for the two. Røiseland and Vabo (2016) believe one of the reasons for this change could be that the production of services and the implementation of public politics became more complex and fragmented. This means that the individual organizations’ chance to shape and implement products has been reduced, and inter-organizational with other public businesses, private companies, or voluntary organizations became necessary. There was a need for new kinds of governance that ensured efficiency within this cooperation.

If one looks at governance from a theoretical perspective, it can also be viewed as a reaction to the encompassing specialisation and decentralisation that was encouraged by New Public Management. Here, the idea had been that more independent companies would take care of their tasks better than larger, multi-functioning management units. As mentioned, the need to coordinate is large today, and much of the literature on government can be seen as an attempt to close the gap between on the one hand scarcer public resources, and on the other bigger expectations and more complicated problems, like the already mentioned patients or users with complex needs (Røiseland & Vabo 2016).

Weaknesses of governance

Of course, like all methods, governance can have its drawbacks: Governance tends to be employed in situations where all participants are seen as more or less equal despite their differences, and in situations where the participants are mutually dependent on one another. Therefore, it can face challenges in conflict-filled situations, where power and/or influence is at stake, and in situations where participants feel like they don’t get any benefits from working together. This is defined as the paradox of governance by Røiseland and Vabo (2016); on the one hand, one of the goals of governance is about overcoming opposing interests and any conflicts that occur. On the other, conflict normally ends up being a hindrance to governance. Perhaps most importantly, troubles can arise when the three solutions either aren’t in place or are hard to implement.

Vik and Hjelseth (2022) are critical towards governance because they believe it is unrealistic, and that the current health system is characterized by differentiation. This means it is split up into parts that are part of a bigger, integrated whole. The way they see it, the problem regarding interaction in the healthcare service is a problem of order – the healthcare system is complex and must be coordinated to suit actors, organizational units, and different knowledge-based and professional environments, that each has their own tasks, interests, and values. This again goes back to the question of how to connect specialized areas into the working whole. The fact that the health sector is divided into units is not inherently a negative thing – on the contrary, it reduces complexity. If for example, you break your arm, you know what needs to be fixed, and who is responsible for making that happen. However, problems occur when the patient has needs that the individual units can’t solve alone but requires them to interact in ways that connect them. The reason for this cooperation is simple: Because it is for the best of the patient, the health services, and society. Furthermore, Vik and Hjelseth (ibid) believe that it is important to challenge the current view on governance, as they believe that the current normative rhetoric can make interaction and social integration harder, as it obscures the tension, opposition, and differences that exist within the modern health service.

A final critique is that governance doesn’t necessarily include everyone that should or could be included in a project, and this lack of inclusion can also be viewed as a democratic issue. Have for example all stakeholders been involved in the project organizations developing the networks? However, Røiseland and Vabo (2016) point out that there are no given guidelines as to what kind of democratic reference point governance should and could be following in the first place. They ask instead if our perceptions of governance should change, as they don’t fit this way of governing.

Governance and democracy

In addition to the three characteristics of communication and knowledge sharing, common goals, and trust, Røiseland and Vabo (2016) also note that democracy is important in the frame of governance. Much like governance, democracy can refer to many different types of leadership, and as such, must be defined. Røiseland and Vabo (2016) define democracy as “representing a certain organization of society where political governance directly or indirectly is under the control of the people” (p. 10). They also write that the biggest challenge democracy has in the framework of governance is achieving the right amount of leadership. As mentioned, governance is ultimately a strategy that involves leading without hierarchy. Therefore, both too much and too little leadership can be an issue. Too much leadership, and governance becomes ineffective because the leader doesn’t have an overview of how to effectively use each parties’ expertise. If there is too little leadership, then this means there is a disconnect between democratic decisions. However, this doesn’t automatically make governance undemocratic. Røiseland and Vabo (2016) reiterate that governance can only be an issue in a democracy if it is purely viewed as “realizing the parliamentary chain of leadership”. If governance is controlled by elected politicians in a sufficient way, then it is democratic.

Governing of governance

A final important question to consider is: What does leadership in cooperation do? It can be said that this consists of two different elements: Structural and rational. Building trust requires leadership, defined as “decentralised, direct, and preferably dialogue-based impact primarily exercised between the single leader and employees” (Røiseland & Vabo 2016: 99), and this requires trust. Unlike hierarchical relationships between leader and subordinate in an organization, the management in cooperation normally has very little formal authority to support themselves on. This makes trust building even more important than in a normal organization. It is the leader's role as the broker of interests that contributes to trust-building in a cooperation, and their work can involve things such as nurturing the relationship between the different parties in the cooperation. Here, there is an implicit ambition to create a common goal and meaning, as well as defining and solving conflicts between those involved.

The leader must also ensure good communication and effective sharing of knowledge. This is something that can already be supported by structural elements such as the process design. This entails the organization of communication between parties and arrangements for the common production of knowledge. The effect the leader has through both governance and leadership sets important premises for what is achievable within the framework of formally organized co-management processes.

Summary

To sum up this theoretical introduction, the following points may be reiterated: As has been mentioned, governance has been a very specific response to challenges that modern Western society faces – of steadily increasing expectations of solving ever more complex societal problems. Complex problems typically involve several autonomous actors that need to cooperate with one another to find a solution. Cooperation is notoriously difficult for several reasons, including 1) different and conflicting perspectives, 2) conflicts regarding what goals are to be achieved and how, and 3) that the cooperation takes place in the relative absence of hierarchy.

Governance, as defined in this report, can be viewed as a response to all of these issues, requiring, however, that certain things need to be put into place. Regarding the first problem – perspective diversity – the solution is communication between the involved parties, and that they together establish a common perception of reality. Secondly, when looking at the problem of conflicting goals, the solution is the development of and support for common goals. Finally, regarding the absence of hierarchy, trust needs to be both established and maintained.

The rest of the report contains five case descriptions of how the three distinct problems of communication, common goals, and trust are handled within five distinct Nordic regional networks. Here, the reader can clearly see how all the involved regions work to ensure that communication and knowledge sharing, common goals, and trust are realized in their project, regardless of what stage it is in.

[1] Veikart for tjenesteinnovasjon. https://www.ks.no/fagomrader/innovasjon/innovasjonsledelse/veikart-for-tjenesteinnovasjon/

[4] It may be noted that there are several different terms that are used when governance is being discussed, i.e. co-governance and new public governance

[5] Leve hele livet: En kvalitetsreform for eldre https://omsorgsforskning.brage.unit.no/omsorgsforskning-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2652620/Leve%20hele%20livet_5_Sammenheng%20og%20overganger%20i%20tjenestene_v2-b.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[6] Is case management effective in reducing the risk of unplanned hospital admissions for older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis https://academic.oup.com/fampra/article/30/3/266/506451