The dream of winning big: Scandinavian Lotto in historical perspective

GamblingJohanne Slettvoll Kristiansen, cultural historian and postdoctoral researcher Published 21 Feb 2024

The popular game of Lotto is commonly believed to have emerged in Scandinavia towards the end of the twentieth century. Recent scholarship examines the forgotten history of how the game reached the Nordic countries much earlier, in the late eighteenth century. It brought with it not only the hope of financial reward and an opportunity to better one’s life, but also much public debate about its possible detrimental effects on people and society. These early debates have proven long-lasting; indeed, we are still grappling with similar questions today.

The 1980s is credited as the decade that saw the emergence of Lotto in Scandinavia. This immensely popular game originated in Italy in the seventeenth century, and finally made its way to the Scandinavian countries only towards the end of the twentieth – at least if we believe the information provided by the Scandinavian gaming companies Svenska Spel, Norsk Tipping, and Danske Spil. According to their webpages, Lotto was introduced in Sweden in 1980, in Norway in 1986, and in Denmark in 1989. Lotto , however, has a much longer, and largely forgotten, Scandinavian history; indeed, it can be traced all the way back to the late eighteenth century.

It happened in 1771

As a curious coincidence, Lotto was introduced in both Denmark-Norway and Sweden (with Finland as part of its territory at the time) in the very same year, in 1771. It was run as a state-operated game until the mid-nineteenth century, when it was abolished, partly for moral and partly for financial reasons. Looking back on this cultural phenomenon many years after its abolition, the Swedish author August Strindberg described the clamor and excitement surrounding the Lotto in the days leading up to the draw in a public square of Stockholm – long before the invention of the televised draw, not to mention the opportunity to purchase tickets online:

What a crowd on Thursday, grown even greater on Friday and culminating in utter frenzy on Saturday! One simply must buy a ticket … One had perhaps pawned a necessary piece of clothing to procure money for the purchase. One had made one’s fine calculations and were almost certain of winning. One saw numbers everywhere, in a coffee cup, in a glass of brandy, among the trash in the streets, and among the clouds.

Strindberg’s depiction points to the widespread magical thinking and cognitive biases informing the belief that you could predict the winning numbers – a powerful notion fueling an industry of books and manuals designed to help you select “lucky” numbers. Indeed, such books and manuals are still available today.

Public entertainment, moral problem, or pragmatic solution?

Strindberg describes a form of public frenzy associated with the Lotto, and he quite fittingly defines the spectacle following its public draws (which took place every third week) as a form of free, urban entertainment (“gratisnöje”).

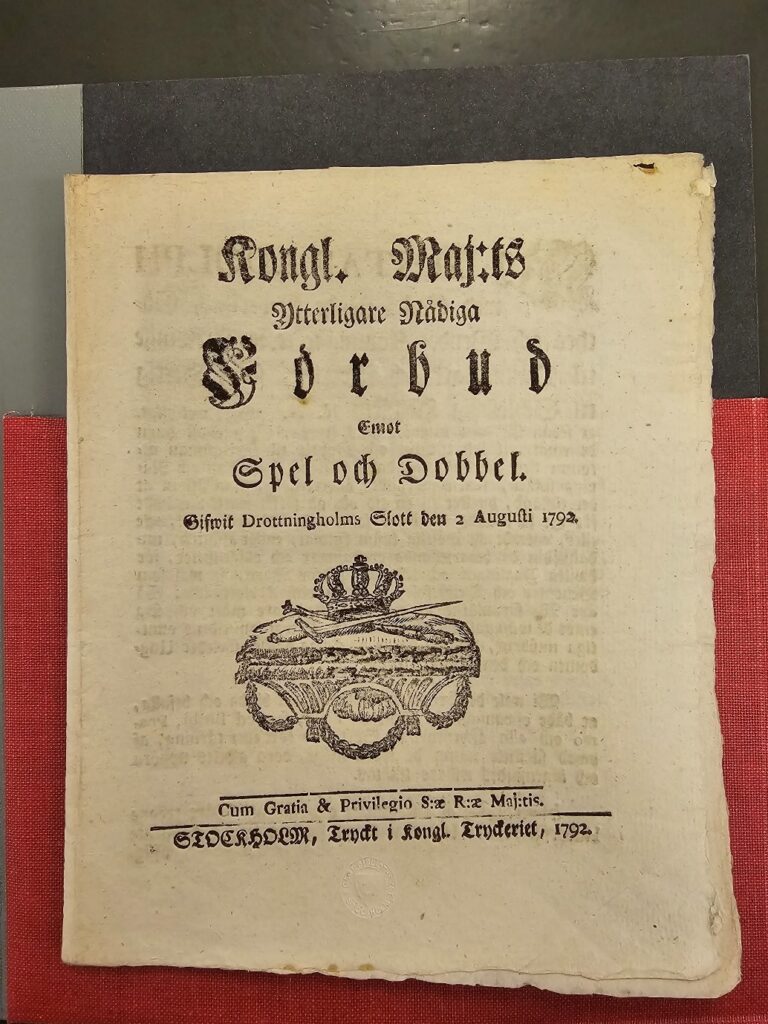

The draws were indeed a form of public entertainment, but they were also a deeply controversial practice that sparked much public debate, not only in the Scandinavian realms but across Europe. State authorities faced a dilemma when it came to the regulation of public gambling: on the one hand having to justify the state-sanctioning of Lotto (essentially a game of hazard) while at the same time prohibiting other and competing forms of gambling, such as cards and dice. Why was one better than the other?

Protecting the people?

The banning of cards and dice was based on the need to protect the people – especially the poor, the young, and the vulnerable – from gambling addiction and personal ruin, which might in turn lead to social tension and public disorder. Those who were critical of Lotto argued that this game brought with it similar detrimental social effects. Lotto may have provided hopes for a better future, but the sad reality was that most people would not win the great prize, despite numerous and ingenious efforts to choose the lucky numbers. Critical voices thus asked how the state authorities could justify taking on the role of lottery operator and gambling facilitator by sanctioning and running a state Lotto, when they claimed to want to protect the people from the evils of gambling.

The dream lives on

The promoters of the state Lotto, on the other hand, highlighted its potential as a significant and convenient source of revenue for the financing of public welfare and infrastructure. It was presented as a way of harnessing, and even tempering, an irrefutable fact: people will gamble. Was it not better, then, if this money could benefit the state and the entire community, rather than going into private and (even worse) foreign hands?

This juxtaposition of financial expediency with sociopolitical and moral concerns has been at the heart of debates connected with state-sanctioned lotteries since their proliferation in the eighteenth century, and it remains a controversial issue today. The dream of “winning big”, which traces its origin back to the eighteenth century at least, has proven to be an enduring motivation for many players. It continues to thrive in our own time, ensuring continued efforts from responsible governments to balance the needs of the state with the wellbeing of its citizens.

This article is written by

Johanne Slettvoll Kristiansen, cultural historian and a postdoctoral researcher based at NTNU in Trondheim, Norway.

on the request of PopNAD