Findings

In this chapter, findings from each of the data sources will be presented separately. First, we shall outline findings from the policy mapping, followed by findings from the online student survey. As a third step, we will summarise insights from young experts, and fourth, present selected promising practices.

Policy mapping

The analysis of the education policy documents was classified into three categories relating to the four elements of the Lundy model: Access and eligibility (space and voice), Role and responsibility (audience), and Structure and activities (influence). In Table 1 below a hyperlink is connected to each of the selected policy document for a full version.

Table 2 Policy document analysis

POLICY DOCUMENTS | CATEGORIES | ||

DENMARK | Access and eligibility | Role and responsibility | Structure and activities |

According to the Executive order from 2014 schools shall establish a student council and that all students in primary schools are eligible to take part in student councils The curricula from 2024 states however that students from grade 5th have the right to form a student council and all students should have voting rights. | The role of the student council is to reflect collective interest of all students. Head teacher or school leaders are responsible for forming and operationalizing student councils and sub-councils in cooperation with students. | Elections to student councils are mandated before October every school year. Student councils shall create bylaws concerning election processes, size of the council, finances and other procedures. | |

ICELAND | Access and eligibility | Role and responsibility | Structure and activities |

All compulsory schools must establish a student council according to the national act and the curriculum. | The role of the student council is to include and promote social, general interest and welfare issues of concern to pupils. Head teachers are responsible for ensuring that the student council receives necessary support. | Student councils are to set their own rules regarding elections and other procedures. | |

SWEDEN | Access and eligibility | Role and responsibility | Structure and activities |

Schools are required to support student associations, facilitating students' ability to organize and express their opinions collectively However, neither the Act nor the curriculum specifically reference an obligatory establishment or operation of student councils. | NA | Student councils are mentioned indirectly in the social studies section for grades 4–6 as an example of democratic decision-making platforms schools can choose to create. | |

FINLAND | Access and eligibility | Role and responsibility | Structure and activities |

Schools must have a student council established by pupils according to the Basic Education Act. | The curriculum states the task of student councils is to promote joint action, involvement, and participation of the pupils. The education provider is responsible for supporting the establishment of a student council or other means for students to express their opinions in matters concerning them. | The curriculum offers pupils’ participation and involvement as a guiding principle for developing the school's operating culture, as well as an obligation to consult students, for example when drawing up a disciplinary plan and a student welfare plan. | |

NORWAY | Access and eligibility | Role and responsibility | Structure and activities |

All schools with students in grades 5th – 10th must have a student council according to the Education Act. | Student councils aim to promote the common interests of students and work towards creating a positive learning and school environment. The National Curriculum states that student councils are to offer children and young people the opportunity to express opinions and make suggestions on matters concerning the students’ local community. | Class-based democratic elections are commonly used to select students into student councils. | |

GREENLAND | Access and eligibility | Role and responsibility | Structure and activities |

The Education Act states that each school shall establish a student council. In smaller schools the student council may include the entire student assembly. | The council shall serve as a forum for discussions on student interests. Pedagogical council shall consult with the student council on all relevant matters. |

THE FAROE ISLANDS | Access and eligibility | Role and responsibility | Structure and activities |

The Public-School Act | At every school with 5th grade or higher, a student council should be established. The school leader involves the students in matters concerning their safety and health. | According to the Executive Order the purpose of student council is to provide students with a place where they can discuss matters of common interest. To develop cooperation and shared responsibility, where students actively participate and address issues through a democratic process. Also, to ensure that students are heard in all matters where decisions are implemented that affect learning, well-being, and educational conditions. | At schools with a student council the method of involvement shall be discussed through the student council. |

Draft (2025) on Executive Order on Student Councils in Primary Schools. Expected to come into force in autumn 2025. | |||

The Faroe Islands National Curriculum NÁM |

The findings summarised in Table 1 show that as regards the elements of space and voice, represented here within the category of access and eligibility, the Nordic countries require schools to establish and support student councils in all primary and lower-secondary schools. According to the policy documents, eligibility typically starts from grade 5 (e.g., Denmark, Faroe Islands and Norway). In most cases, all students are able to either vote or participate indirectly in student councils, ensuring broader representation (e.g., Denmark, Finland, Faroe Islands and Iceland). An interesting legal example is offered by Greenland, which allows for the option of an entire student assembly to form a student council in smaller schools, reflecting a flexible and contextualised approach. Sweden is currently the only Nordic country which does not mandate student councils, rather it encourages student organisation generally. In this sense, student councils are mentioned in the national curriculum as one of good ways of working towards students’ democratic participation.

In terms of the element of audience, represented here within the category of role and responsibility, student councils in the Nordic region are primarily tasked with promoting the interests, welfare, and voices of students (e.g., Faroe Islands, Iceland and Norway). Student councils often operate in relation to school or municipal councils, ensuring students a wider audience beyond their class or school (e.g. Denmark, Finland, Iceland). They are often understood as a platform to consult on school policies (e.g., Finland) and a space for democratic participation (e.g., Finland, Faroe Islands and Iceland). In most cases student councils are governed by head teachers or school leaders, who are expected to play a supportive and facilitative role, ensuring councils are formed and operated effectively (e.g., Denmark, Iceland, Norway).

Finally, with regard to the element of influence, represented here under the category of structure and activities, Denmark and Norway require formal elections and structural democratic procedures in operating a student council. Commonly, class-based elections are used to select 1–2 representatives to student councils, who are then able to set their own bylaws (Denmark). This includes forming their own mandate and list of activities (Iceland). In Finland, student councils are embedded into the schools’ operational culture and have recently been connected to the idea of transversal competencies such as sustainability, human rights, and democratic participation. Structures such as pedagogical councils in Greenland and student council discussions in Faroe Islands emphasise the role of student councils as part of broader school governance.

Student survey findings

The ten-question student survey was submitted to students in the Nordic countries, asking them about participation in student councils, knowledge on their aims and tasks dealt with, as well as experiences of trying to have influence on school issues. As mentioned in the chapter on methods, it was not possible to collect the same number of responses among the participating countries. The total number of responses after data cleaning amounted to 278 from Denmark (46% girls; 54% boys), 303 from Finland (47% girls; 53% boys), 638 from Faroe Islands (50% girls; 50% boys), 23 from Greenland (48% girls; 52% boys), 917 from Iceland (48% girls; 52% boys), 8 from Norway (0% girls; 100 % boys), and 69 from Sweden (64% girls; 36% boys). In Greenland and especially Norway, the numbers of responses were very few and for that reason the results from those countries will not be interpreted. The numbers of 5th-grade students and 10th-grade students were similar in all countries except for Finland, where most respondents were 10th graders, and Norway, where all respondents came from grade 5.

Existence of student councils and students' participation

When students were asked if there was a student council in their school, most students reported that this was the case (91–99%). The exception was Iceland, where the percentage was 73% (see Table 3).

Table 3 Existence of a student council

Is there a student council at your school? | ||

Denmark | ||

Yes | 96% | |

No | 4% | |

I don’t know | 0% | |

Faroe Island | ||

Yes | 96% | |

No | 2% | |

I don’t know | 2% | |

100% | ||

Finland | ||

Yes | 91% | |

No | 3% | |

I don’t know | 6% | |

100% | ||

Greenland | ||

Yes | 91% | |

No | 0% | |

I don’t know | 9% | |

100% | ||

Iceland | ||

Yes | 73% | |

No | 6% | |

I don’t know | 21% | |

100% | ||

Norway | ||

Yes | 100% | |

No | 0% | |

I don’t know | 0% | |

100% | ||

Sweden | ||

Yes | 99% | |

No | 1% | |

I don’t know | 0% | |

100% | ||

Students were also asked if they had been on a student council (See Table 4).

Table 4 Been on a student council

Have you been on a student council? | ||

Denmark | ||

Yes | 32% | |

No | 68% | |

Faroe Islands | ||

Yes | 26% | |

No | 74% | |

Finland | ||

Yes | 28% | |

No | 72% | |

Greenland | ||

Yes | 57% | |

No | 43% | |

Iceland | ||

Yes | 24% | |

No | 76% | |

Norway | ||

Yes | 25% | |

No | 75% | |

Sweden | ||

Yes | 29% | |

No | 71% | |

As seen in table 3, roughly one third of the surveyed students had been part of a student council. The lowest participation rate, 24%, came from Iceland.

Students’ responses on the length of time they had been on the council showed that regardless of the country of residence most students reported having participated between six months and up to three years. Some students mentioned not recalling how long they had participated. A similar trend was identified across all the Nordic countries: most students participated in student councils during their teenage years, but there were also several students younger than this.

Choosing members of student councils

Students were asked if they were able to describe how students were elected for the student councils. There was a great deal of variation in their knowledge (Table 5).

Table 5 Knowledge on how students are elected for student councils

Can you describe how students are elected for the student councils? | ||

Denmark | ||

Yes | 86% | |

No | 14% | |

Faroe Islands | ||

Yes | 75% | |

No | 25% | |

Finland | ||

Yes | 49% | |

No | 51% | |

Greenland | ||

Yes | 26% | |

No | 74% | |

Iceland | ||

Yes | 41% | |

No | 59% | |

Norway | ||

Yes | 100% | |

No | 0% | |

Sweden | ||

Yes | 59% | |

No | 41% | |

Table 5 shows that the majority of students in Denmark (86%) were well informed about the choosing process for student councils. This was also the case in the Faroe Islands, where the percentage was 75%. In Sweden, around 60% knew how students get selected to participate in student councils. The percentage was 50% in Finland and around 40% in Iceland (Table 5).

When students were asked open questions to further describe how student council participants were chosen, most of them explained that some kinds of democratic processes were used. Students in Denmark described that a classmate willing to participate generally volunteered, campaigned, or gave a speech. Voting took place in anonymous ballots or by open voting. However, some described how their school used random selection, with teachers generally guiding or monitoring the selection.

Students from Faroe Islands described elections of student council members typically involving self-nomination, candidate presentations, and typically anonymous classroom voting. However, among many students there were also concerns about popularity bias and lack of structure or fairness related to electing participants. This suggests there is room for improvement in transparency and accountability.

Finnish students also said that voting was the most common method of selecting students for the student councils, but there was significant variation between schools. Some schools used applications, others favoured interviews, and some used random draws. Although many viewed the process as democratic and fair, others expressed concerns about lack of clarity or consistency and the teachers’ key role in the selection. As was already mentioned, few responses were collected from Greenland. However, their open answers were in line with those of the other countries in that democratic classroom-based elections were the most common way of getting into student councils. These included a process of students voting or deciding together who should represent them. Written ballots were mentioned as an example of the process, but there were also examples where students were not fully aware of or involved in how the selection for student councils worked in their school.

In Iceland, most students reported that joining the student council involved some form of democratic selection, such as elections or application-based processes. The process varied slightly across schools but generally included representative elections within each class. Students were either nominated or voted for, typically selecting one boy and one girl. Some schools used applications where staff members choose candidates based on their interests and qualifications. Others described random drawings if too many were interested in being on the council. In some cases, students could also choose the student council as a subject where they can get credits for participating, especially in the higher grades. Some students raised fairness concerns, mentioning the need for greater consistency, transparency, and fairness in the selection process. These concerns were raised in relation to teacher influence in the process. One student mentioned having been on the student council when Covid-19 hit the world and described having missed out on the experience of being on the council as there were no meetings during the pandemic. Thereafter the student had not been chosen by administration to be on the council:

Quote from student " I was [in the student council] …, but because of Covid-19, I didn't get to be there for long, and I'm really mad at the school for not giving me another chance…. I was also sick a lot, but that's my problem, but their [problem] is that they postponed [student council meetings] a lot. |

In Greenland and Norway, answers were few but students typically described democratic voting or random drawing as methods of selecting students for the student councils. There were also some less democratic exceptions, which pointed to the need for more structure in the selection process.

In Sweden, students commonly reported using voting when choosing between class representatives, usually at the start of the school year. Typically, the classmates nominated themselves or others, and everyone voted – sometimes with attention to gender balance. Another option was open discussion about who to nominate, often led by teachers. Some responses point to possible bias or dissatisfaction, especially related to teacher favouritism. It was suggested that the process needed to be made more transparent.

Issues typically addressed by student councils

Students were asked in the survey if they could describe what issues the student council work on (see Table 6).

Table 6 Issues dealt with in student councils

Can you describe issues dealt with by the student councils? | ||

Denmark | ||

Yes | 68% | |

No | 32% | |

Faroe Islands | ||

Yes | 53% | |

No | 47% | |

Finland | ||

Yes | 41% | |

No | 59% | |

Greenland | ||

Yes | 35% | |

No | 65% | |

Iceland | ||

Yes | 34% | |

No | 66% | |

Norway | ||

Yes | 75% | |

No | 25% | |

Sweden | ||

Yes | 61% | |

No | 39% | |

Denmark and Sweden had the highest percentage of students saying they could describe what the student councils do, followed by students from Faroe Islands. A notable number of students from Finland, Greenland and Iceland were not sure about the role of student councils.

Students who said that they were able to describe what the councils do were asked to give examples of the council’s projects. Students mentioned that the meetings between students and staff related to the student councils created a positive venue for them to share ideas and push for positive change. In general, the most common tasks mentioned in all countries were organising social events and making the school a better place by amplifying student voices. Practical ideas were most often mentioned such as ideas on running school cafés, fundraising, furniture needed, and improvements for the playgrounds. However, some also mentioned helping to improve the overall school atmosphere and improving well-being in the school.

In Sweden, the student councils were generally viewed as a platform for student representation where class issues and ideas are discussed and, at times, acted on. Students appreciated having a voice, especially regarding school policies, trips, and classroom conditions. They said they understood that not all requests can be met, as some requests are unrealistic and the schools have limited resources. There were also responses that highlighted the importance of strengthening the councils’ framework and ensuring inclusivity, democratic, and respectful communication within the councils, and support from school employees.

Norwegian students described the role of the student councils as working on issues to improve the school environment especially with peer support and inclusion in mind. They reported that student councils can play a supportive role for the school community. However, numerous students said they had limited knowledge or awareness of the student council. They were consequently not fully aware of their role.

Audience to student councils' proposals

Half of the students or more said that their audience were teachers and the administration, who generally listened to their ideas. In Denmark, 80% of students said that school leaders and teachers took student council proposals into consideration.

Table 7 Audience to student councils’ ideas

Do you think school leaders and teachers consider proposals from student councils? | ||

Denmark | ||

Yes | 80% | |

No | 20% | |

Faroe Islands | ||

Yes | 50% | |

No | 50% | |

Finland | ||

Yes | 63% | |

No | 37% | |

Greenland | ||

Yes | 22% | |

No | 78% | |

Iceland | ||

Yes | 53% | |

No | 47% | |

Norway | ||

Yes | 86% | |

No | 14% | |

Sweden | ||

Yes | 58% | |

No | 42% | |

A much deeper and a more nuanced picture emerged of students’ attitudes, when their open-ended responses were examined. While the administration in the Nordic countries generally listened to students on the student council and while the students felt it was useful to meet staff members to discuss school matters and reforms, many students expressed a desire for clearer outcomes of their ideas.

Danish students emphasised that this would boost students’ trust in the effectiveness of their inputs. They explained that the most common suggestions acted upon were related to practical matters such as getting a new microwave, planning a school event or trip, improving the playgrounds, seating in the classroom, and increasing food options. When it comes to other and more complicated proposals many students express frustration over ignored ideas, unrealistic promises, and lack of transparency. Many students also cited incidences of poor communication within the councils themselves, inconsistent processes, and a lack of follow-through with ideas.

Similarly, students in Norway and Sweden expressed mixed views on how seriously their suggestions were taken. While some felt heard and respected, there was lack of consistency and follow-through. Students also felt that some ideas are acknowledged or implemented while others are not, often depending on feasibility. Sometimes the processes are so long that by the time action is taken, the students who proposed the action have moved on. The Finnish students added to this and outlined that more persistence, clarity, and active communication is needed between students and the school staff. However, students underlined their understanding that not all ideas can be accepted. Some are unrealistic and the schools’ resources are limited.

Student council influences

Students were asked if they could describe issues student councils have had real impact on in their schools (see Table 8).

Table 8 Knowledge of issues student councils have had influence on

Can you describe issues that student councils have had influence on at your school? | ||

Denmark | ||

Yes | 44% | |

No | 56% | |

Faroe Islands | ||

Yes | 50% | |

No | 50% | |

Finland | ||

Yes | 36% | |

No | 63% | |

Greenland | ||

Yes | 9% | |

No | 91% | |

Iceland | ||

Yes | 22% | |

No | 78% | |

Norway | ||

Yes | 17% | |

No | 83% | |

Sweden | ||

Yes | 31% | |

No | 69% | |

Table 8 shows that 22–50% of students could describe issues where student councils had made a difference. Students from all countries gave several examples of the influence exerted by these councils on preparing events such as talent shows and renewing sports equipment. Danish students also mentioned various issues such as upgrading cafeteria areas and making changes related to meals. Students from the Faroe Islands said the school councils had had a positive impact, particularly on playgrounds, restrooms, and getting rest areas and sofas in the school.

Similar findings emerged from Finland: student councils were identified as critical in giving opportunities to enhance school life, particularly through organising events and improving various student matters. Other examples related to improving play areas, well-being, and occasionally influencing school rules.

However, it is important to note that only a small proportion of students believed they could have a real impact on their school. In their answers they often also expressed doubts about student councils’ visibility and felt that its impact was limited. Swedish students reported mixed experiences with their student councils and their perceived influence. The experiences varied greatly, depending on communication within the councils themselves and with administration, and follow-through. A desire for a more meaningful impact and clearer outcomes was evident as students expressed frustration or uncertainty about the process.

According to the open answers, Greenlandic students felt the councils functioned as a key link between students and school staff, especially in forwarding concerns or needs. They said that meetings played a central role in the planning and decision-making involved in organising meaningful activities such as study trips. However, not all students were fully clear on the council’s role, suggesting room for improved communication or visibility. Similar emphases were evident in the responses of the Norwegian students who saw the student councils as contributing to school life through planning fun events and adding enjoyment and a variety of experiences to enrich their schooling.

Summary of student survey findings in the Nordic countries

Space: selection process

Across the participating countries, student council selection is widely framed by democratic principles, with voting being the most common method. Students value having a voice in choosing their representatives and participating in school decision-making. However, there were concerns about the lack of structure, transparency, consistency in working methods, and bias when selecting representatives to the councils. In addition, findings mention communication issues and lack of criteria within the councils to ensure the inclusion and well-being of all participants.

Across the participating countries, student council selection is widely framed by democratic principles, with voting being the most common method. Students value having a voice in choosing their representatives and participating in school decision-making. However, there were concerns about the lack of structure, transparency, consistency in working methods, and bias when selecting representatives to the councils. In addition, findings mention communication issues and lack of criteria within the councils to ensure the inclusion and well-being of all participants.

Voice: issues dealt with

Student councils are valued across the countries for representing student voice and improving the school environment. The most frequently mentioned issues are related to events and practical questions. Students nevertheless wish to strengthen the student council’s role as an effective body for student voice. Anyone within the student councils can express themselves and make suggestions on issues that they consider are meaningful and significant to improving student well-being.

Student councils are valued across the countries for representing student voice and improving the school environment. The most frequently mentioned issues are related to events and practical questions. Students nevertheless wish to strengthen the student council’s role as an effective body for student voice. Anyone within the student councils can express themselves and make suggestions on issues that they consider are meaningful and significant to improving student well-being.

Audience: communication and resources

Most students generally feel their voices are heard by school staff, especially through the student council. Listening is valued by students even when not all ideas are accepted. Teachers are often seen as more responsive than school leaders. Students also stated that communication and consultation between students and school staff needs to be increased as well as the follow-through of student proposals so that the student councils have a stronger and a more trusted role in shaping the school life. Across all contexts, students frequently express frustration that their suggestions are not consistently implemented. While some practical ideas lead to change, students report that many others are stalled due to slow processes. Also, students desire clearer communication on what happens after ideas are submitted. A lack of transparency in how student council ideas are handled – especially in the Faroe Islands, Finland, and Iceland – leads to doubt, disengagement, or scepticism about the council’s impact. In addition, many students (especially in Finland, Faroe Islands, Iceland and a few in Greenland) don’t fully understand the student council’s role, suggesting a need for improved visibility and information-sharing within schools. In the Faroe Islands and Sweden, some students mention that council representatives don’t always consult classmates or that they fail to act on shared concerns, highlighting a gap between representation and inclusion.

Most students generally feel their voices are heard by school staff, especially through the student council. Listening is valued by students even when not all ideas are accepted. Teachers are often seen as more responsive than school leaders. Students also stated that communication and consultation between students and school staff needs to be increased as well as the follow-through of student proposals so that the student councils have a stronger and a more trusted role in shaping the school life. Across all contexts, students frequently express frustration that their suggestions are not consistently implemented. While some practical ideas lead to change, students report that many others are stalled due to slow processes. Also, students desire clearer communication on what happens after ideas are submitted. A lack of transparency in how student council ideas are handled – especially in the Faroe Islands, Finland, and Iceland – leads to doubt, disengagement, or scepticism about the council’s impact. In addition, many students (especially in Finland, Faroe Islands, Iceland and a few in Greenland) don’t fully understand the student council’s role, suggesting a need for improved visibility and information-sharing within schools. In the Faroe Islands and Sweden, some students mention that council representatives don’t always consult classmates or that they fail to act on shared concerns, highlighting a gap between representation and inclusion.

Influence: meaningful activities

Student councils were recognised as a good way to improve school life, but across all countries, students express lack of follow-through on students’ ideas. Students also reported that they receive little information about what happens to their proposals, and those that are put forward often take a long time to process, so that students may even have completed their studies when the changes are implemented. While many students recognise and appreciate tangible changes such as new equipment or social activities, others express frustration with limited follow-through. Students often doubted the actual influence of student councils; according to their answers, the perceived influence of the councils depends largely on how well they communicate, how visibly they implement changes, and how consistently they follow up on student suggestions.

Student councils were recognised as a good way to improve school life, but across all countries, students express lack of follow-through on students’ ideas. Students also reported that they receive little information about what happens to their proposals, and those that are put forward often take a long time to process, so that students may even have completed their studies when the changes are implemented. While many students recognise and appreciate tangible changes such as new equipment or social activities, others express frustration with limited follow-through. Students often doubted the actual influence of student councils; according to their answers, the perceived influence of the councils depends largely on how well they communicate, how visibly they implement changes, and how consistently they follow up on student suggestions.

Insights from young young experts

Nordic Baltic Youth Summit

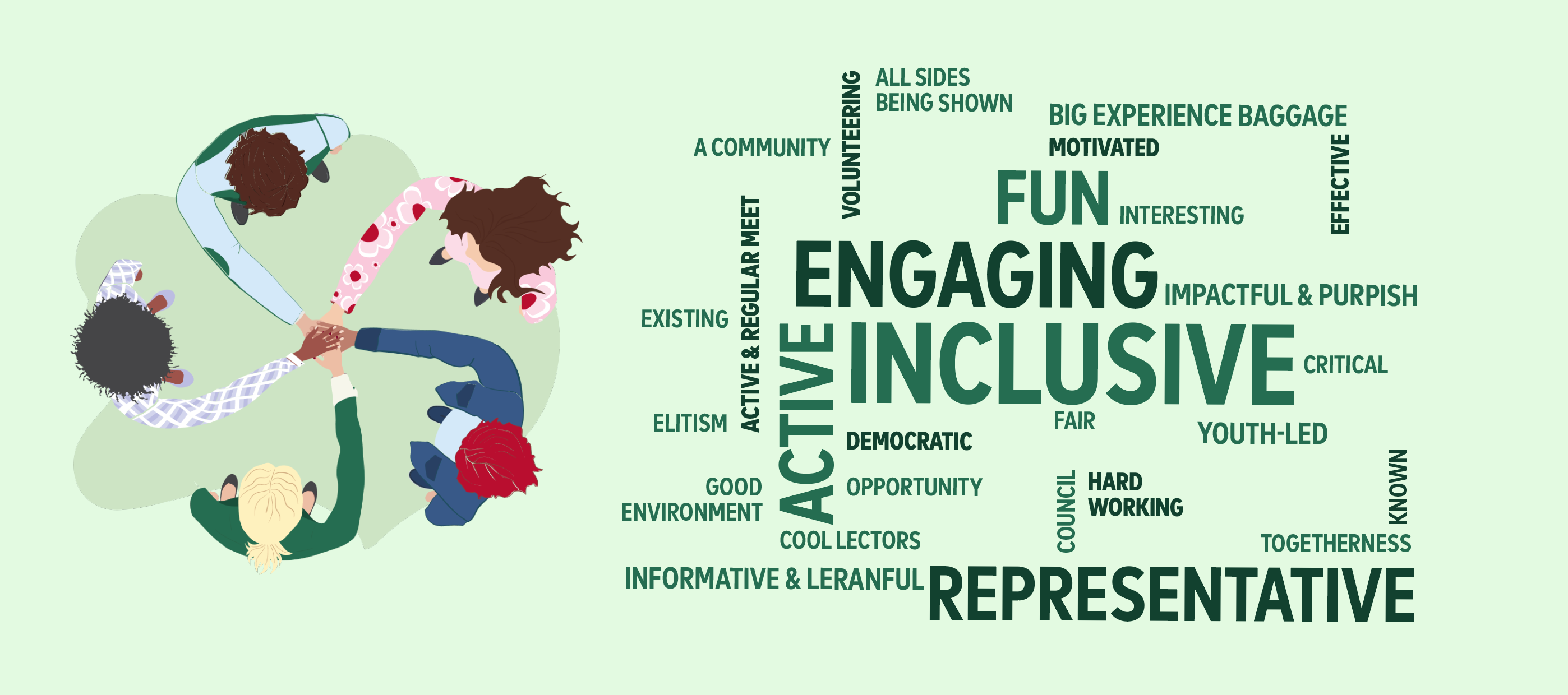

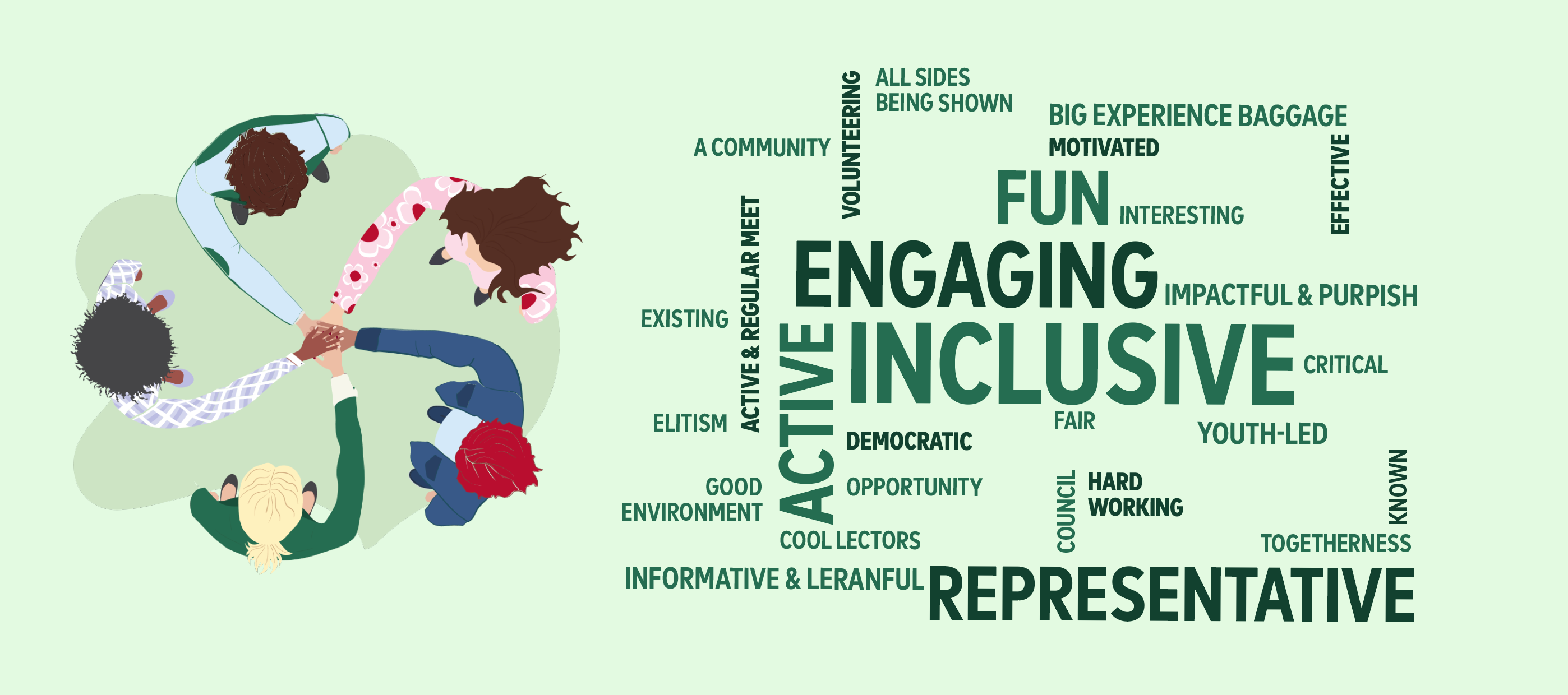

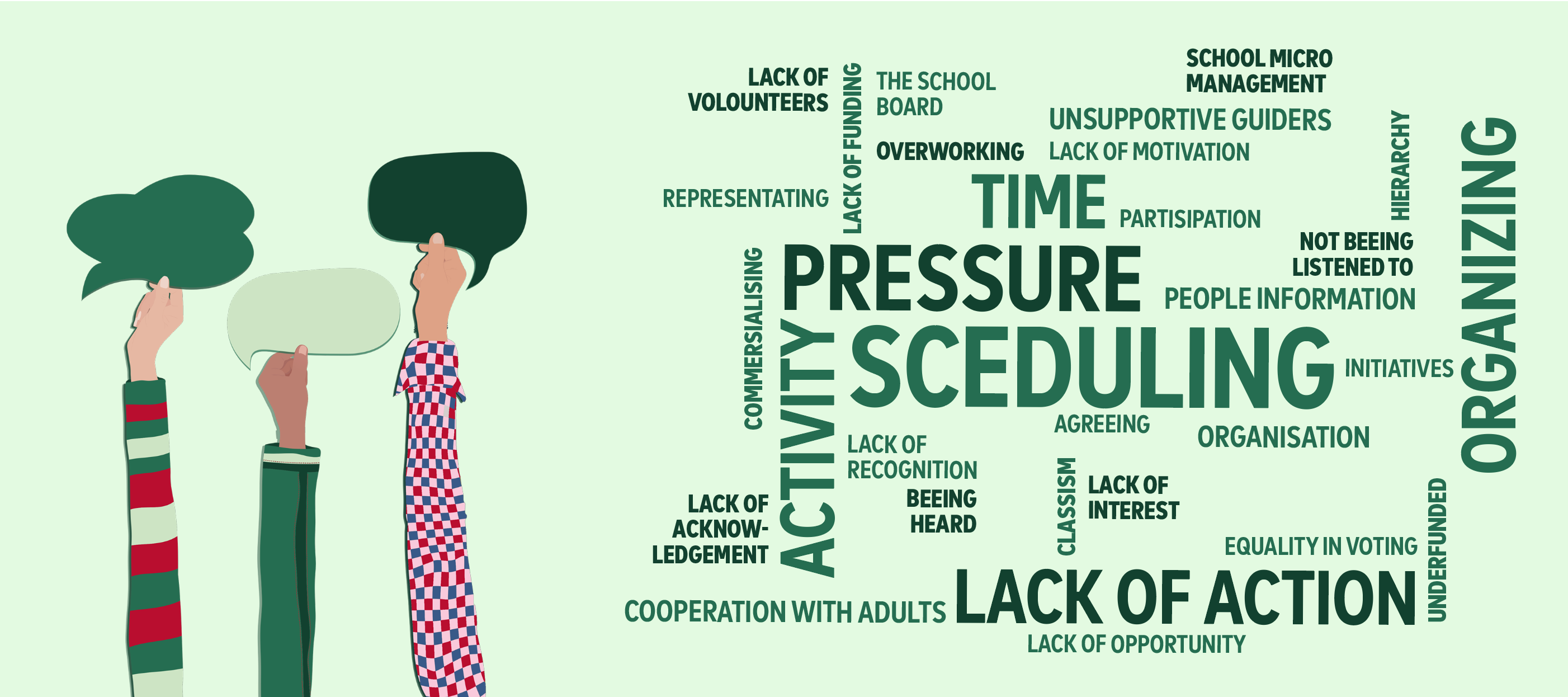

In September 2024, the Nordic Baltic Youth Summit took place in Vilnius, Lithuania. During the summit, information about student councils was gathered from the participants through questions posted online and in informal discussions. Most of the young people engaged in the summit spoke positively about their experiences of participating in a student council in their lower- or upper-secondary schools. When asked to describe the ‘ideal’ student council, the respondents emphasised inclusivity and representation along with aspects of engagement and meaningful activities. When asked to offer one concept or term to describe the biggest challenge student councils face, the students raised several issues from lack of recognition to the opportunity to be heard. These questions were featured prominently along with ideas of elitism or non-democratic processes despite the formal election system in place in most Nordic schools. Figures 2 and 3 below display the words most often used in relation to the two questions posed during the summit.

Figure 2 Word-cloud presenting young experts’ ideal student councils

Figure 3 Word-cloud presenting the biggest challenges of student councils according to young experts

Promising practices in student participation and inclusion

For this study, we sought examples of unique and promising practices from across the Nordic region to illustrate how student councils can become meaningful platforms for participation when grounded in inclusive practices supported by principles from the Lundy model.

The following case studies are not meant to be compared, copied, or borrowed without due consideration of how temporal and relational factors impact all policy and practical implementation within the context of education (Steiner-Khamsi, 2024). We do however hope that they are a source of inspiration to students, teachers, and policymakers alike, as they came across as having a great potential to us.

Activating the school yard: Enhancing students’ physical and social well-being (Finland)

In one Finnish school, the student council’s typical role in organising social events evolved into a broader initiative to improve students’ health and well-being. During a regional gathering of student council representatives known as ‘winter days’, students discussed common concerns and shared ideas for promoting student engagement. An idea that emerged was to transform their own schoolyard, which was largely paved with asphalt and was widely regarded by students as dull and demotivating.

In response, the student council organised equipment and materials such as board games and sports gear to revitalise recess activities and energise both body and mind during short breaks. This initiative reflects multiple elements of the Lundy model: space (a transformed, engaging environment for students), voice (students identified the problem and solution), audience (school leaders supported the initiative), and influence (the idea was implemented with visible impact).

Importantly, this practice highlights the value of peer exchange beyond individual schools, where young people inspire and learn from one another across contexts. It also demonstrates how democratic participation can impact students’ everyday experiences in meaningful ways.

Linking school councils with local governance: A child-friendly municipality (Denmark)

In one Danish municipality recognised as child-friendly under the UNICEF framework of child-friendly cities, strong ties have been established between student councils at the school level and the municipalities’ youth councils. This structure creates a continuum of participation that enables children and young people to influence decisions both within and beyond their schools.

A key feature of this model is its intentional focus on inclusion. The municipality actively works to ensure participation by students who are traditionally underrepresented, such as children of different ages and those with disabilities, by creating safe spaces for diverse voices. The councils collaborate on initiatives at some schools, like planning activities for World Children’s Day, driven by students themselves and grounded in shared democratic values and Article 12 of the UNCRC.

Students report feeling listened to by school leaders, who regularly coordinate with other schools and municipal officials to promote children’s voices and influence. Training sessions equip young people with the knowledge and confidence to contribute meaningfully to discussions about their learning environments, fulfilling all four elements of the Lundy model and promoting long-term capacity building for democratic participation.

Open access to amplify diversity and representation (Iceland)

Two Icelandic schools have made deliberate changes to student council selection processes to challenge the often-exclusive nature of peer voting systems. Teachers and students in both schools identified how traditional election models tended to favour socially prominent or outgoing individuals, marginalising those who didn’t fit the normative frame, including migrant students and students with disabilities.

In one school, student council membership was made entirely open to any student in grades 8 to 10, without formal elections. Although the council operates without a fixed time or space, and meetings are arranged on an ad-hoc basis, this model ensures low barriers to entry and gives students significant autonomy over their participation.

In the second school, a more structured system invites all students to apply for student council membership and to submit a brief statement outlining their interests and ideas for council activities. The student council meets regularly during the school year, and members are assigned specific roles aligned with their preferences and plans. This not only increases participation but also creates a more deliberate structure for meaningful engagement based on students’ ideas and reflections.

Both schools now report broader representation and greater inclusivity, indicating that alternative access models can strengthen student voice, challenge normative assumptions about leadership, and contribute to more democratic and responsive school governance.