Discussions

This report set out to examine the status, role, and perceived impact of student councils in primary and lower-secondary schools across seven Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Our analysis was guided by principles of democratic and citizenship education (Biesta, 2006; Edelstein, 2011; Guðjohnsen, in press) and youth participation (Lundy, 2007).

Drawing from policy mappings, a student survey, youth summits, and focus group interviews, we found a complex and often uneven landscape of student participation across the Nordic countries. The discussion is organised around the proposed research questions, integrating insights from the literature, Covid-19 experiences, and the data collected for this study.

Characteristics of regulation of student councils in the Nordic region

Policy mapping revealed that, except for Sweden, all Nordic countries legally mandate the establishment of student councils in primary and lower-secondary schools. Access to and participation in student councils is usually considered from 5th grade onwards, though in some cases policies mention eligibility of all students. Moreover, policy documents across the Nordic region clearly emphasise the importance of democratic educational processes, representation, and consultations of students. These are in line with the Nordic Council of Ministers’ Vision 2030 to ensure children participation in accordance with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, 1989).

However, as discussed by Gunnulfsen et al. (2021), implementation often falls short of the ideals of inclusive and effective participation. Our findings show that despite the policy mandate, many students across the Nordic region are unfamiliar whether or not there is a student council in their school and to what extent it functions on their behalf. Even fewer report having participated in the work of a student council. Participation ranged between 24% and 32% of the surveyed students, with variations by country. Clearly there is a gap between the universal access to democratic platforms within schools, mandated in the policy documents, and the actual lived realities of young people in Nordic schools. While the figures can be read to indicate a reasonable level of involvement, the data also reflects broader systemic issues of unequal participatory opportunities (Griffin, 2022; Harðardóttir & Jónsson, 2021).

For example, in both policy and practice, an emphasis is placed on prioritising older students’ participation in student councils. This was evident especially in the findings where the students who reported having participated were mainly in the older age group of 13–16-year-olds and when they spoke about issues student councils were in charge of (i.e. planning events for older students). Such findings indicate that student councils are often overlooked as platforms where younger children can be involved and have a say on many important educational and social issues related to their well-being at school.

While Nordic education policy documents uniformly advocate for democratic schooling, the uneven realisation of student participation underscores the need for ongoing critical reflection, capacity-building, and commitment to genuine participatory culture. The contrast between the progressive Nordic education model and realities of everyday student participation highlights a structural gap, reinforcing critiques from democratic education scholars (Blossing et al., 2014; Jónsson et al., 2021). This is particularly the case during extraordinary times such as the Covid-19 pandemic, as discussed in earlier reports (Helfer et al., 2021; Løberg, 2023), where lack of robust participatory structures became evident and showed the need for a more resilient system to safeguard children’s rights in crises and throughout.

Selection processes often lead to unequal participatory opportunities

The student survey indicated that democratic elections are the dominant selection method across schools in the Nordic countries. In some countries, including Denmark and Norway, formal regulations mandate structured elections and operational rules in relation to the selection process. Similar selection processes were also described as part of the qualitative data gathering, during focus group interviews, and by young Nordic experts.

However, critical concerns were raised by young people across the Nordic region that formal democratic selection processes were lacking in transparency and fairness. Many raised the issue of student councils being prone to popularity contests: students who are elected are described to have a strong socio-economic background or to be in obvious power positions within the school. Additionally, students reported how those elected tend to hold on to their seats and sit for longer periods, impeding other students’ opportunities for participation. The legitimacy of student councils in schools, therefore, cannot rest only on formal democratic processes such as elections but must reach deeper to ensure inclusivity and fairness.

The role of staff-working with the student councils often appeared unclear. In some cases, students reported how teachers or school leaders would influence council membership in ways that undermined students’ agency and diminished their trust in the democratic potential of student councils. These barriers reflect broader tensions within the context of education between idealistic visions of citizenship education and democratic participation on the one hand and marketised realities of contemporary education on the other (Dovemark et al., 2018; Jónsson, 2016; Guðjohnsen, in press).

Such findings further align with those of previous research (Griffin, 2022; Kempner & Janmaat, 2023) on how traditional structures can inadvertently marginalise certain groups and how superficial democratic forms often mask deeper inequalities (Biesta, 2006; Edelstein, 2011). Reports from students feeling disconnected to decision-making spaces and processes, particularly among those students with disabilities or from marginalised backgrounds, emphasise the importance of considering questions of access to participatory structures within schools in terms of equity and inclusion.

Such reports were strikingly visible during the Nordic Youth Disability Summit, where students with disabilities and minority backgrounds voiced limited participation opportunities within Nordic lower-secondary schools. They also mentioned lack of relevance in councils’ agendas causing a sense of mistrust towards conventional participatory structures within the context of education. Their experiences are in line with broader trends showing disengagement and lack of interest in student councils in the Nordic region (ICCS, 2022) and in a wider perspective decreasing trust in public institutions (Haggard & Kaufman, 2021; Jafarova, 2021). Moreover, their accounts made visible structural and cultural barriers within a perceived democratic and equal Nordic education model (Blossing et al., 2014). The pandemic further exposed these gaps, as noted by Helfer, Aapola-Kari and colleagues (2023), who highlighted the lack of clear participatory avenues and the need to include a broader group of students — not just a few representatives — in decision-making processes such as student councils. This limited inclusivity led to the exclusion of many young people from meaningful participation.

Issues, activities and perceived impact

Findings on what issues students address in a student council further mirror critiques by scholars who claim that student participation is often limited to ‘low stake’ issues rather than critical civic engagement (Biesta & Lawy, 2006; Guðjohnsen, Jordan et al., 2024a; Westheimer, 2014). While fun activities are important to students’ participatory experiences and school culture, as noted by young experts informing this study, there is a risk of missed opportunities to develop deeper democratic engagement and development opportunities (Aðalbjarnardóttir, 2007; Sund & Pashby, 2020).

This phenomenon can also be understood within the broader context of marketisation and instrumentalisation of education (Dovemark et al., 2018; Jónsson, 2016), where the emphasis on individual success and short-term outcomes sidelines deeper civic, socio-economic, and cultural issues. As a result, student councils, risk being relegated to organising superficial and predictable activities rather than serving as forums for real democratic engagement, reinforcing concerns raised by Magnússon (2019) and Slee (2011) about the exclusion of critical and diverse voices in education. If student councils are understood in such simplified and tokenistic manner, their impact is equally limited (Griebler & Nowak, 2012).

Our findings show that students feel moderately heard by teachers and school leaders but experience significant frustration over the slow follow-through on suggestions and issues raised within the student council. Again, our findings are consistent with those of previous studies: student councils often serve more symbolic than functional roles. As noted earlier, the Covid-19 experience further underscored the urgent need for more meaningful and responsive communication mechanisms where students’ voices are sought in critical matters concerning their education (Donbavand & Hoskins, 2021; Løberg, 2023).

Key areas supporting inclusive and meaningful participation in student councils

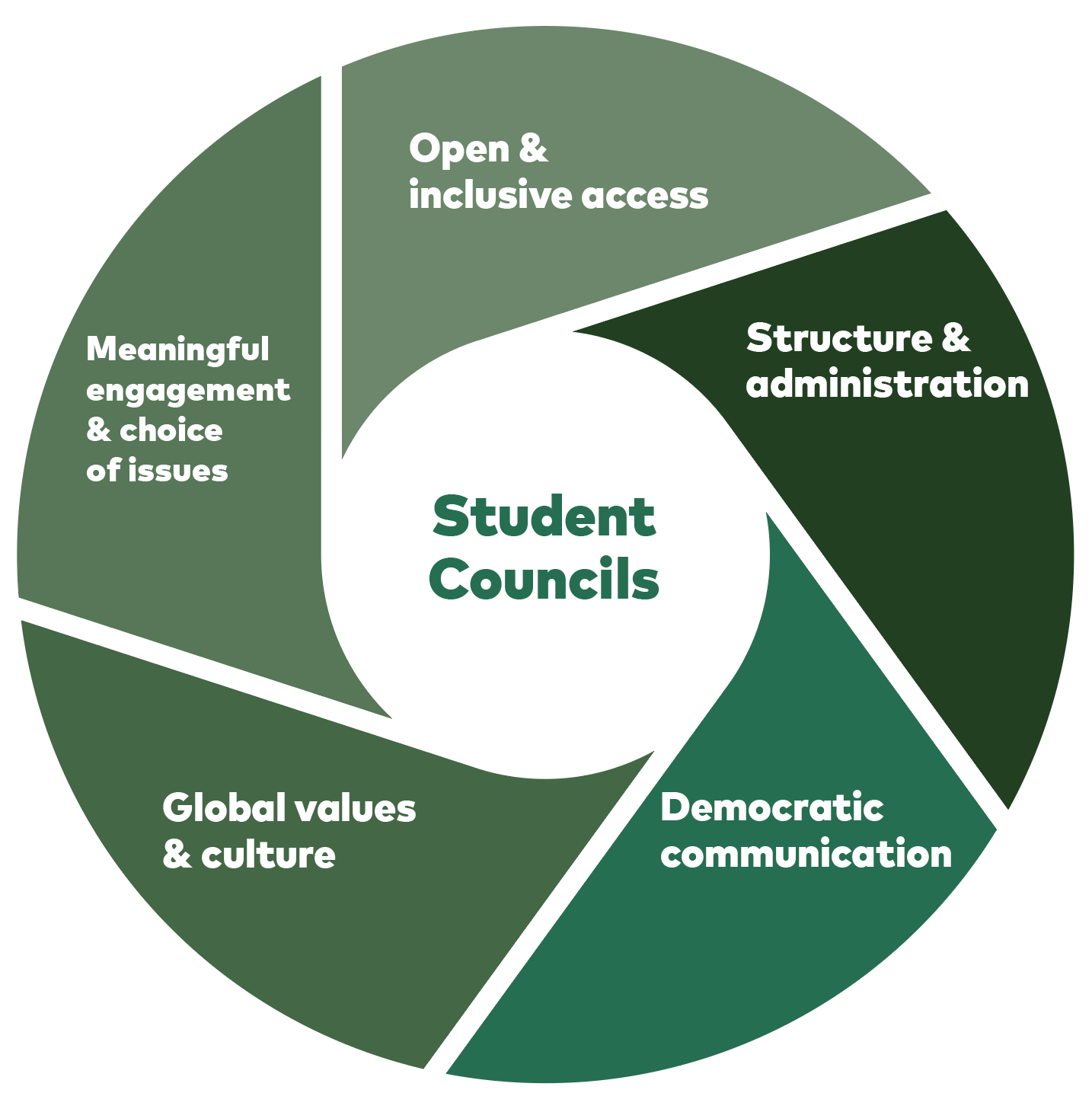

The findings of this study highlight key factors that are essential to ensuring that student councils in Nordic schools, function as meaningful platforms for democratic participation and civic engagement. Drawing together the data and literature, we identified five interconnected themes as crucial for strengthening student councils.

Figure 4 Model on student councils’ participation

Open and inclusive access

Ensuring that all students, regardless of their age, background, ability, or social standing, can access and participate in student councils is fundamental for promoting genuine democratic participation within schools. Traditional election methods, often relying on majority voting, risk excluding already marginalised voices, while open, hybrid, and flexible participation models could actively encourage representation from a wider spectrum of the student body, including younger students, students with disabilities, minority language speakers, and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Structural supports, such as ensuring physical and communication accessibility, are equally essential. By embedding inclusive practices into the fabric of student council operations, schools move closer to fulfilling the commitments outlined in both the UNCRC and the Nordic Council of Ministers’ Vision 2030, ensuring that student representation reflects the diversity and complexity of contemporary school communities.

Supportive structures and administration

The role of school leadership is pivotal. Administrations must not only establish councils, as stated in regulations, but also genuinely support and empower them. This requires moving beyond tokenistic practices to provide resources, structured time, and adult allies who champion student agency while respecting students’ autonomy. Leadership teams and educators must commit to engaging with council proposals in a timely and transparent manner, explaining decisions and highlighting where student input is expected to lead to change. It became clear that many schools are independently ‘reinventing the wheel’ rather than building on visible and shared structures. This approach often results in isolated efforts rather than systematic support for meaningful participation. Greater collaboration between schools and the establishment of more common guidelines or frameworks for student council work could strengthen consistency, legitimacy, and the overall democratic culture across the education systems. As the Covid-19 experience showed, resilient and supportive administrative practices are essential in safeguarding participatory rights in times of crisis (Løberg, 2023).

Democratic communication

To ensure that councils are meaningful rather than symbolic, communication must be structured, reciprocal, and transparent at three critical levels: within the council, within the school community, and across schools or regional networks. Within councils, it is essential to foster inclusive and participatory dialogue where every member, regardless of background or confidence level, feels empowered to voice their opinions. Clear meeting procedures, rotating chair roles, training in democratic deliberation, and respectful facilitation practices can help ensure that discussions are not dominated by a few voices. Within the wider school community, effective communication involves establishing strong, visible links between the student council and the broader student body. Councils must actively seek input from classmates, either through class representatives, regular feedback sessions, surveys, or open forums. Equally important is the provision of systematic feedback to the student body about how ideas are considered and what outcomes result. At the regional or communal level, fostering communication between councils in different schools offers significant potential for strengthening student participation. Networks of student councils, either formalised through municipal youth councils, cross-school working groups, or regional forums, can facilitate the exchange of ideas and collective advocacy on issues that transcend individual schools.

Meaningful engagement through diverse issues

The data revealed that student councils often focus on organising social events or minor facility improvements. While these activities are valuable, there is a need to broaden councils’ mandates to address systemic, educational, and well-being issues that truly matter to students’ lives. Addressing more diverse issues such as inclusion, mental health, and sustainability can strengthen students’ sense of ownership, relevance, and efficacy in school life, countering trends of marketisation and instrumentalisation in education (Dovemark et al., 2018). By ensuring that councils address a wide range of concerns, reflecting the lived experiences of students from different socio-economic and cultural backgrounds and with different experiences, student councils can move towards becoming truly representative forums where all students see their realities and aspirations meaningfully reflected.

Global values and civic culture

Student councils should be embedded within broader goals of education for sustainability and global citizenship. While many councils focus on local issues, a deliberate integration of sustainability, human rights, and social justice topics would foster students’ sense of global responsibility and deepen their understanding of interconnected civic realities (Sund & Pashby, 2020; Jónsson & Garces Rodriguez, 2021). Such a shift holds potential to move councils from isolated and often superficial school activities to forums where global democratic values are explored and enacted.